Victor Pasmore, 1908 – 1998

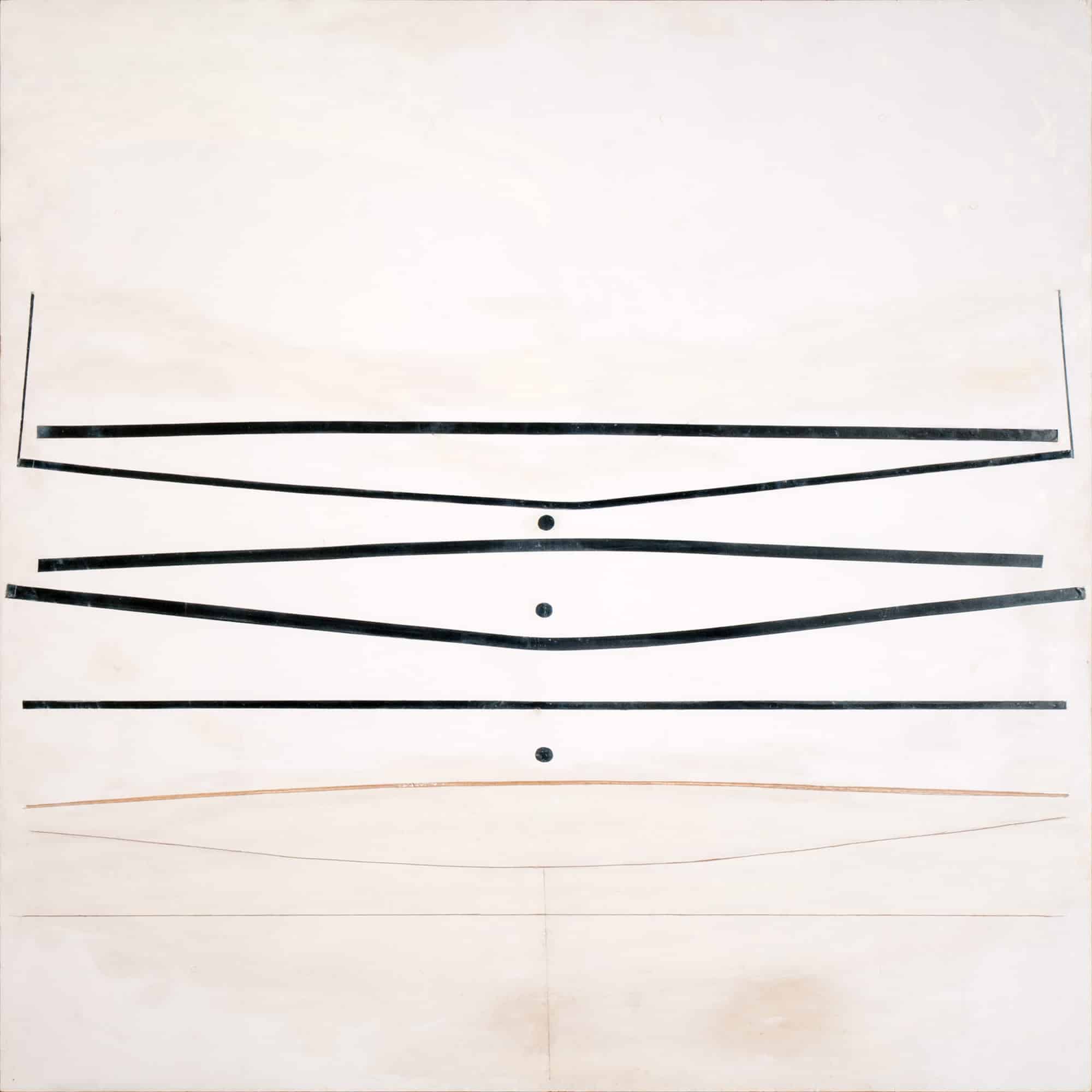

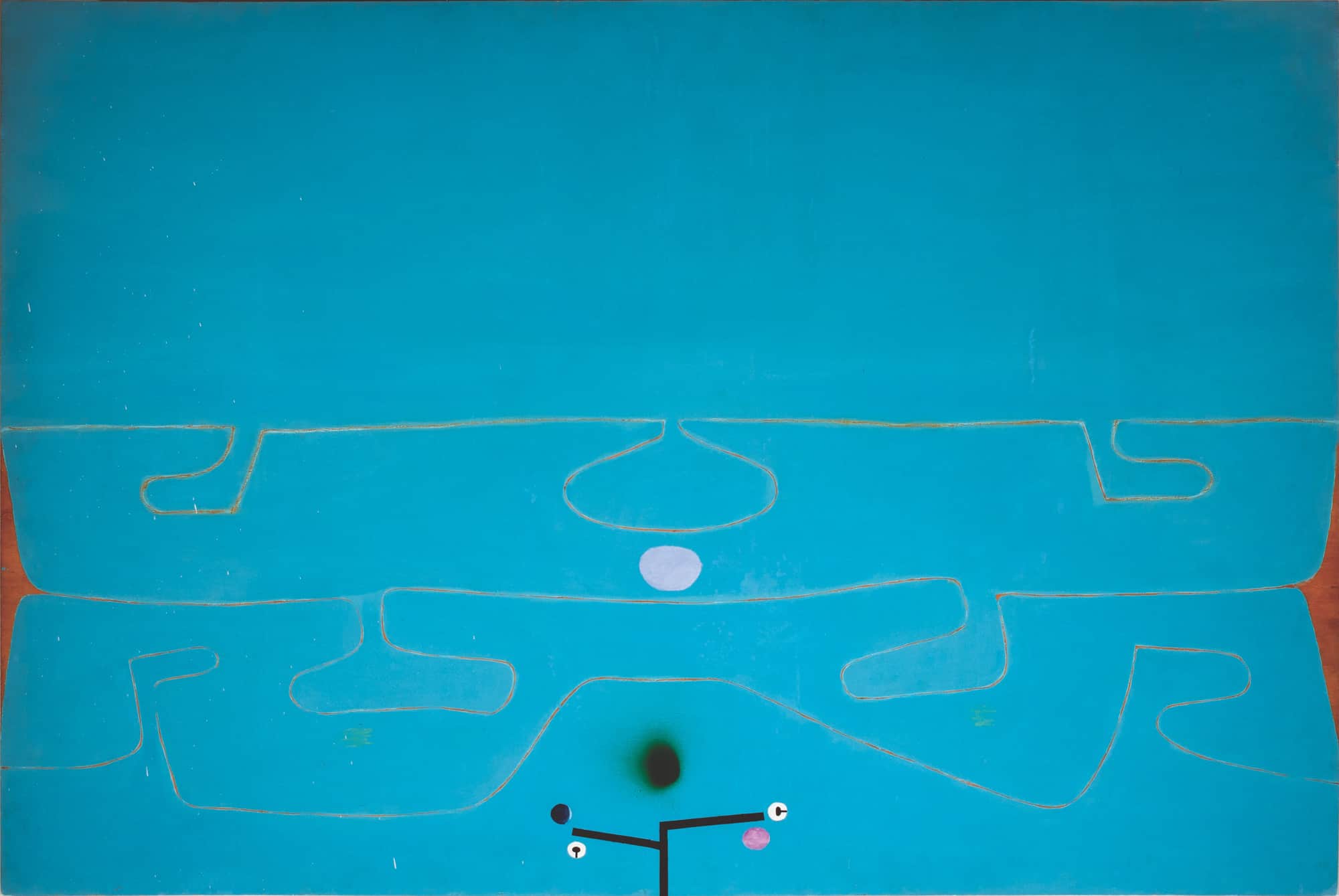

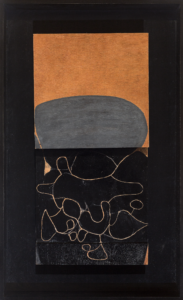

“Did not the naturalist tradition use perspective in order to produce an illusion of space and solidity? This suggested that the surface format of painting could not provide the conditions necessary for complete independence unless combined with sculpture or architecture. In response to this, therefore, I continued with development or relief projection.”

Victor Pasmore, ‘The Transformation of Naturalist Art and The Independence of Painting’, Constructions and Graphics: 1926-1979, 1980.

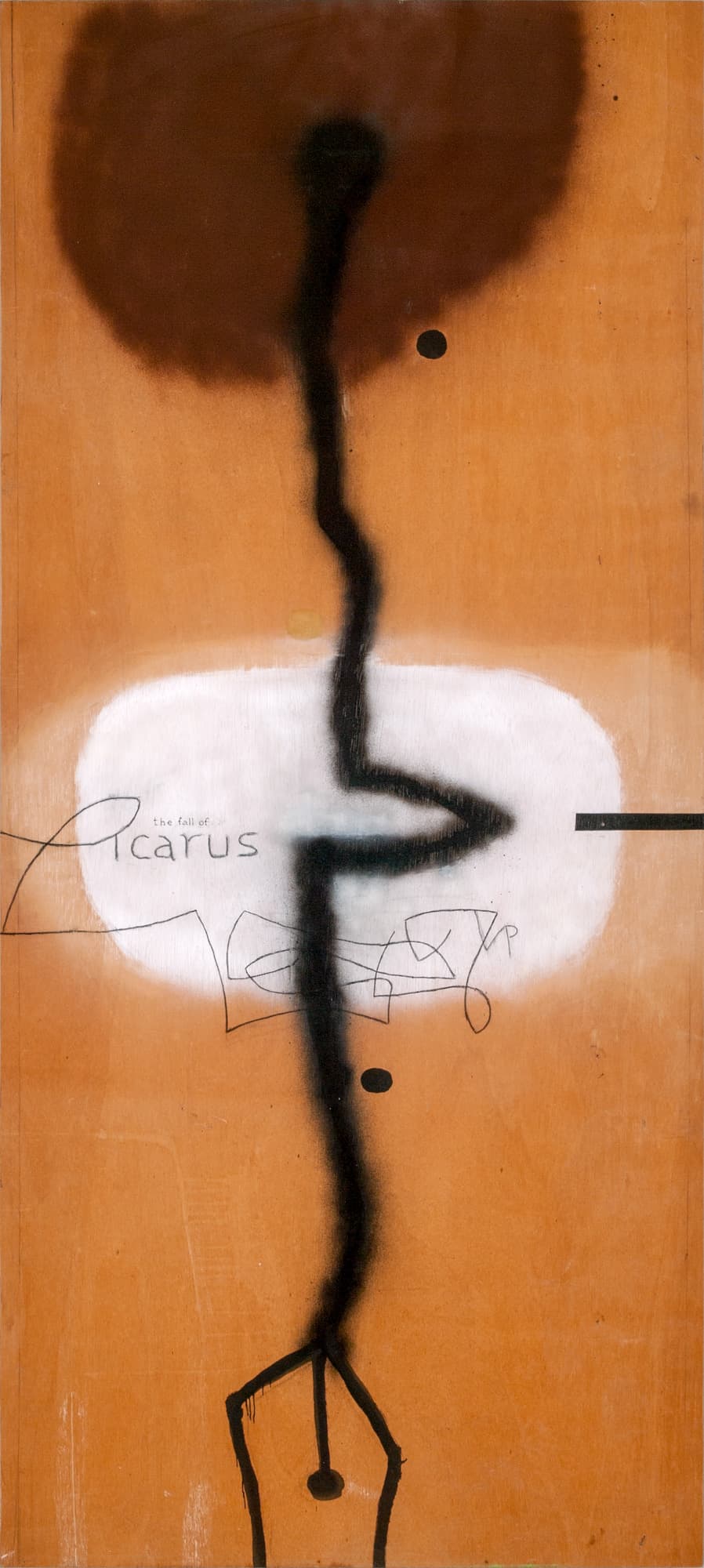

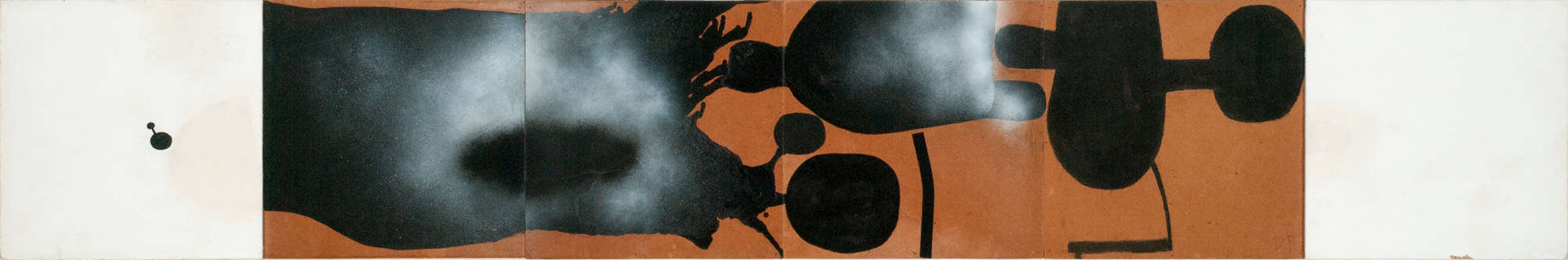

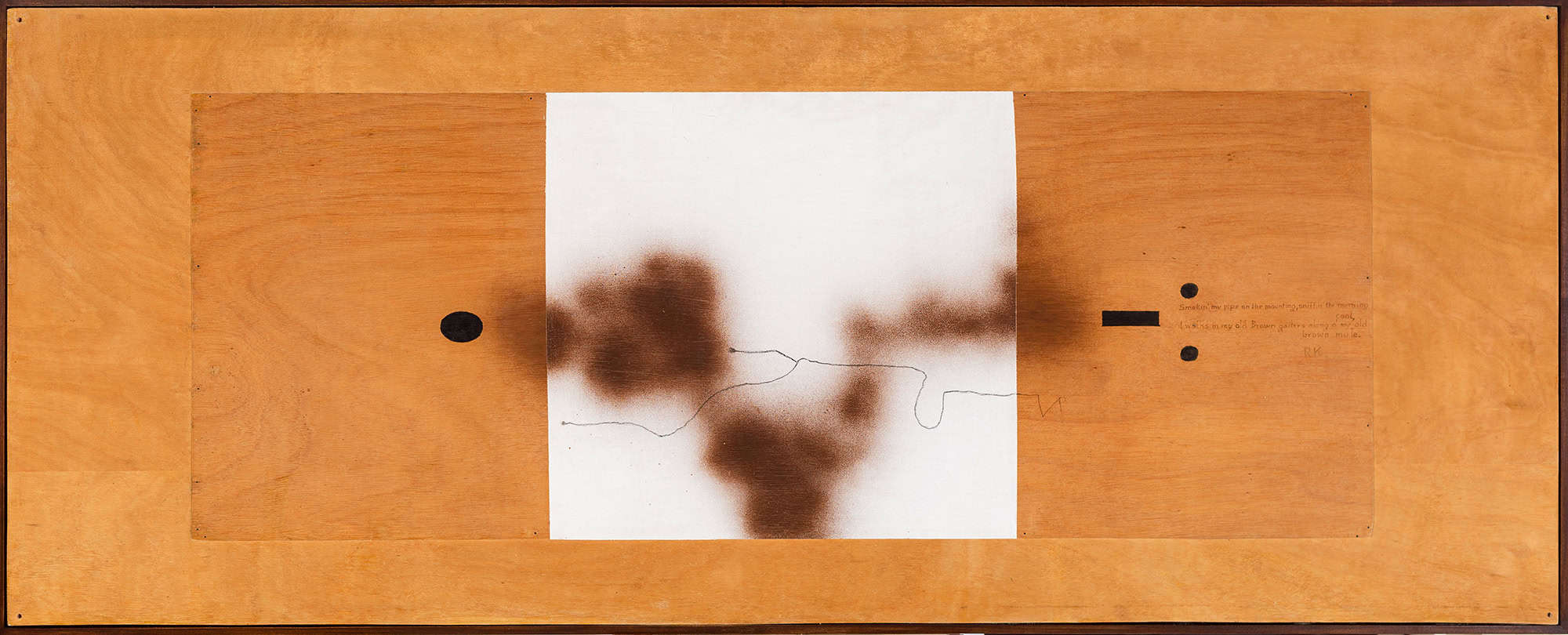

“I just had a plywood board. I had it in the Academy this year… The Bird, the harmony of opposites. Something that will kill the bird. It’s a threat. The bird will never escape.”

Cathy Courtney, ‘Artists’ Books: Victor Pasmore Talks’, Art Monthly, n.191, November 1995.

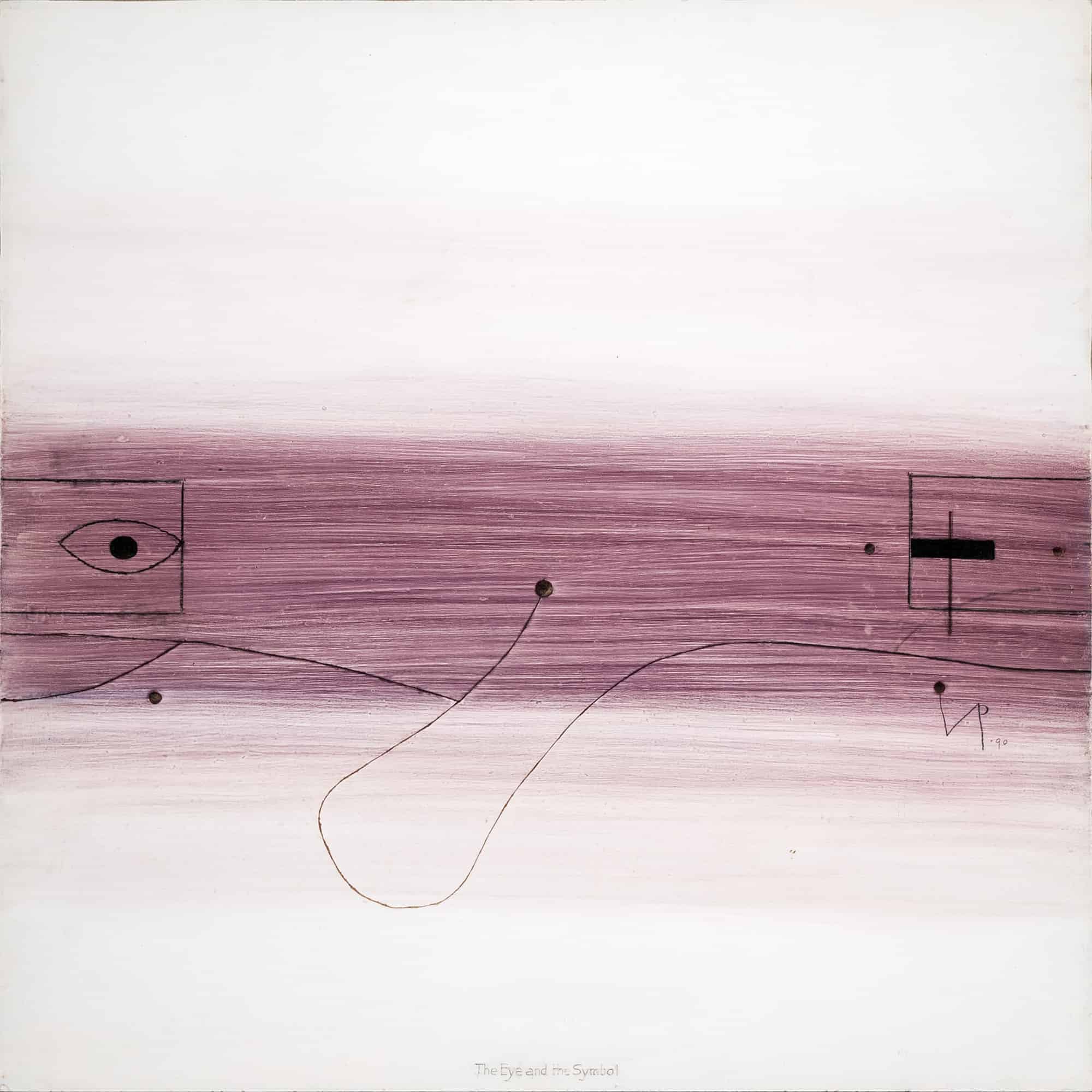

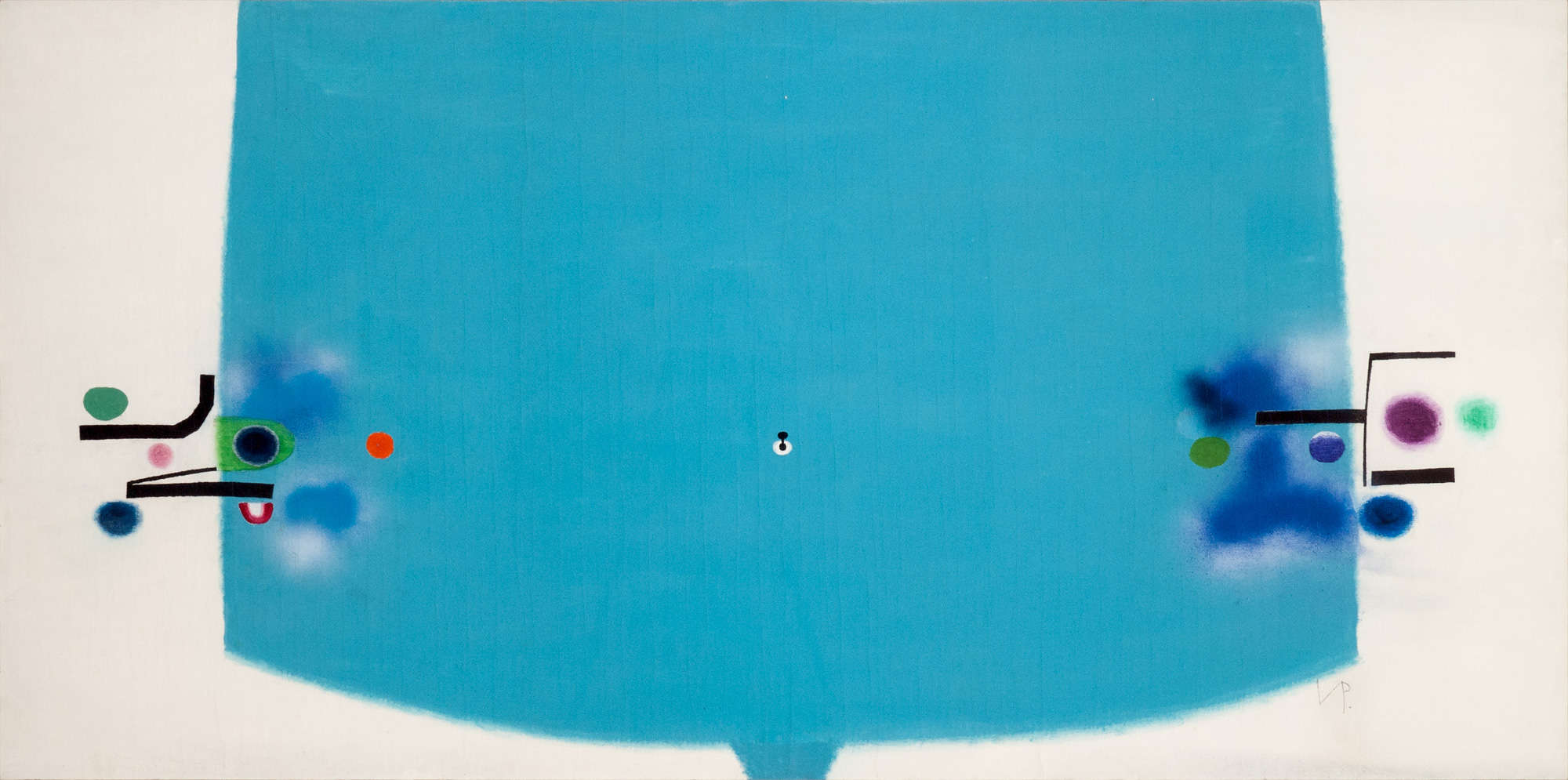

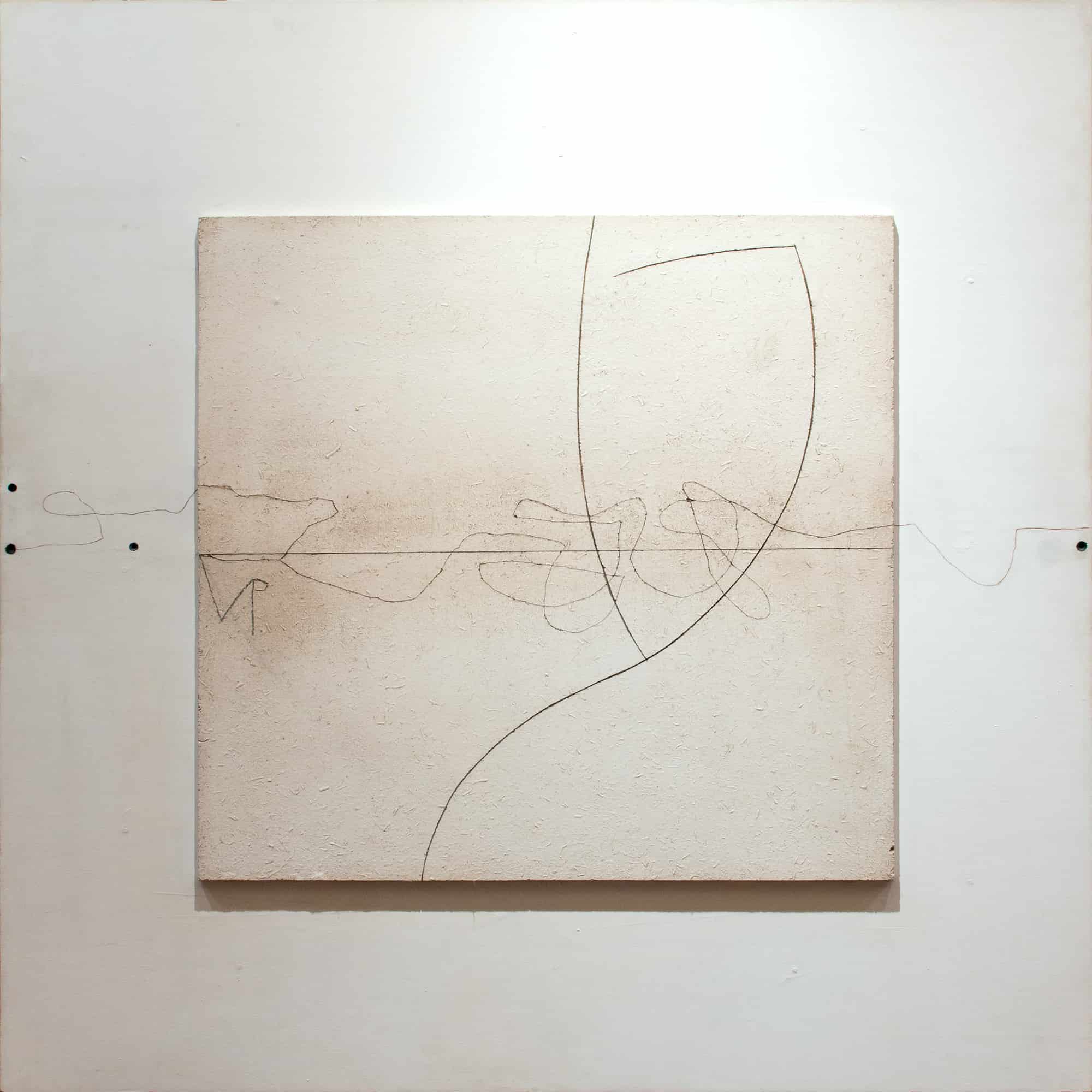

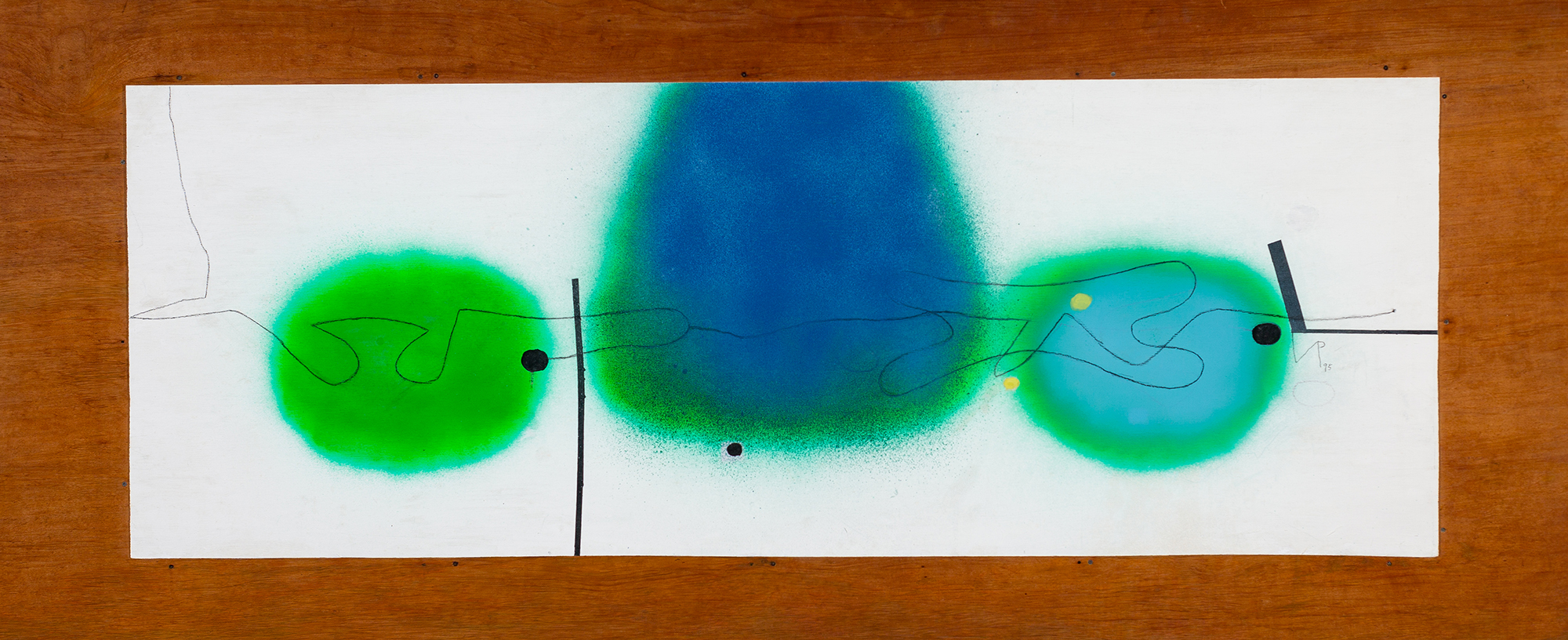

“Once independent, a painting becomes the sole visual object so that its content becomes totally immanent in its form and image, a condition which renders its meaning essentially potential. Emerging in anonymity, therefore, the new painting can become a sign or symbol of infinite extension, directly finding its place in the eye and mind of the spectator.”

Victor Pasmore, ‘Images of Colour’, 1983.

“Abstract work will be unable to find its most powerful form in the surface-bound medium of painting alone. Because of its inherent nature, abstract painting cannot revert to conceptual illusionism. Consequently it is confined to a two-dimensional format. The abstract painter therefore, inevitably finds his path of development blocked. But the cause of this blockage is not the idea of abstraction itself, but the physical limitation of pictorial material.”

Victor Pasmore, ‘What is Abstract Art?’, The Sunday Times, 5 February 1961.

“In the past, religious painting provided a link between sensibility and the mystery of God, but now the link is with Nature.”

Victor Pasmore, ‘The Artist’s Eye’, 1990.

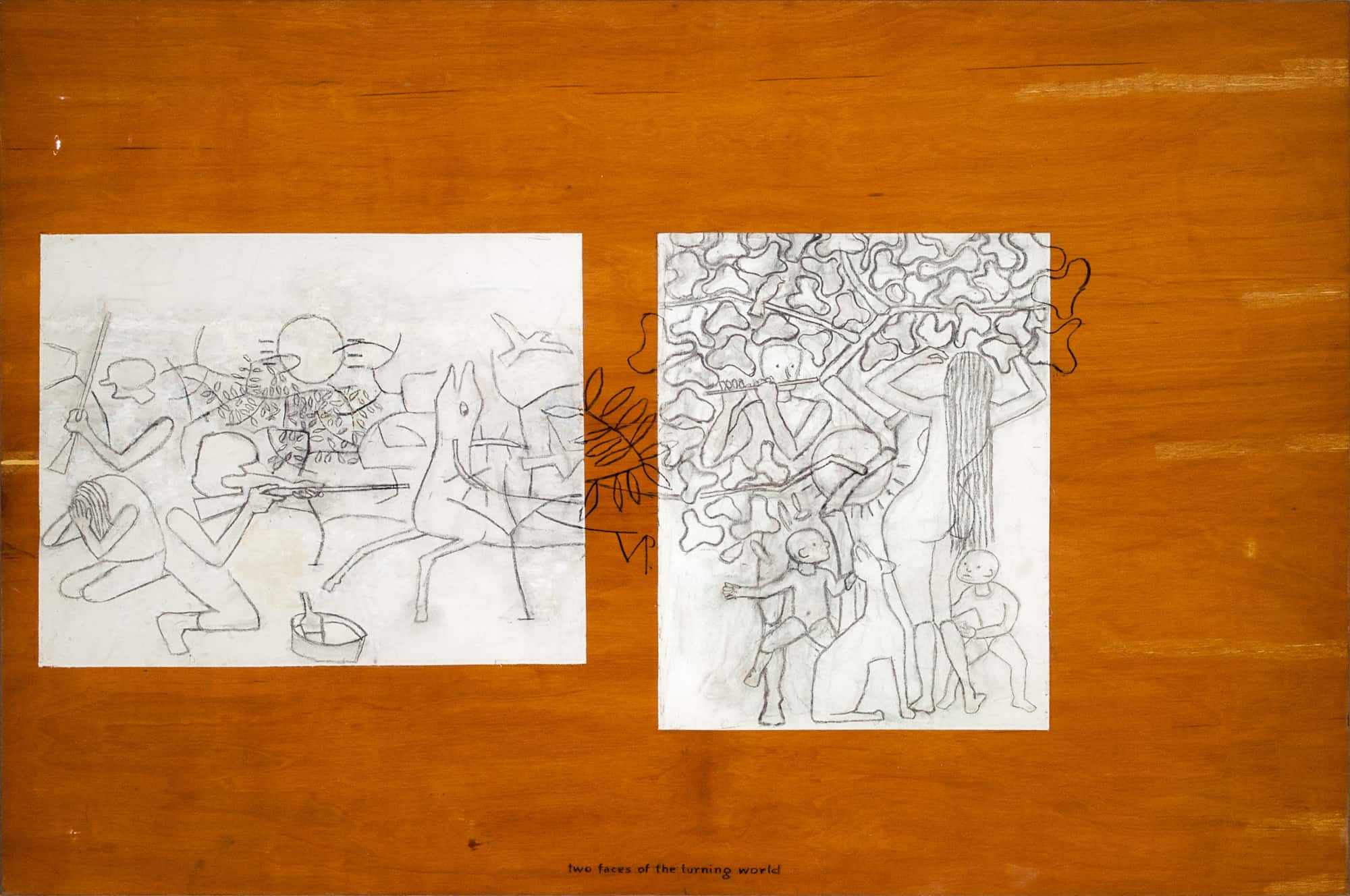

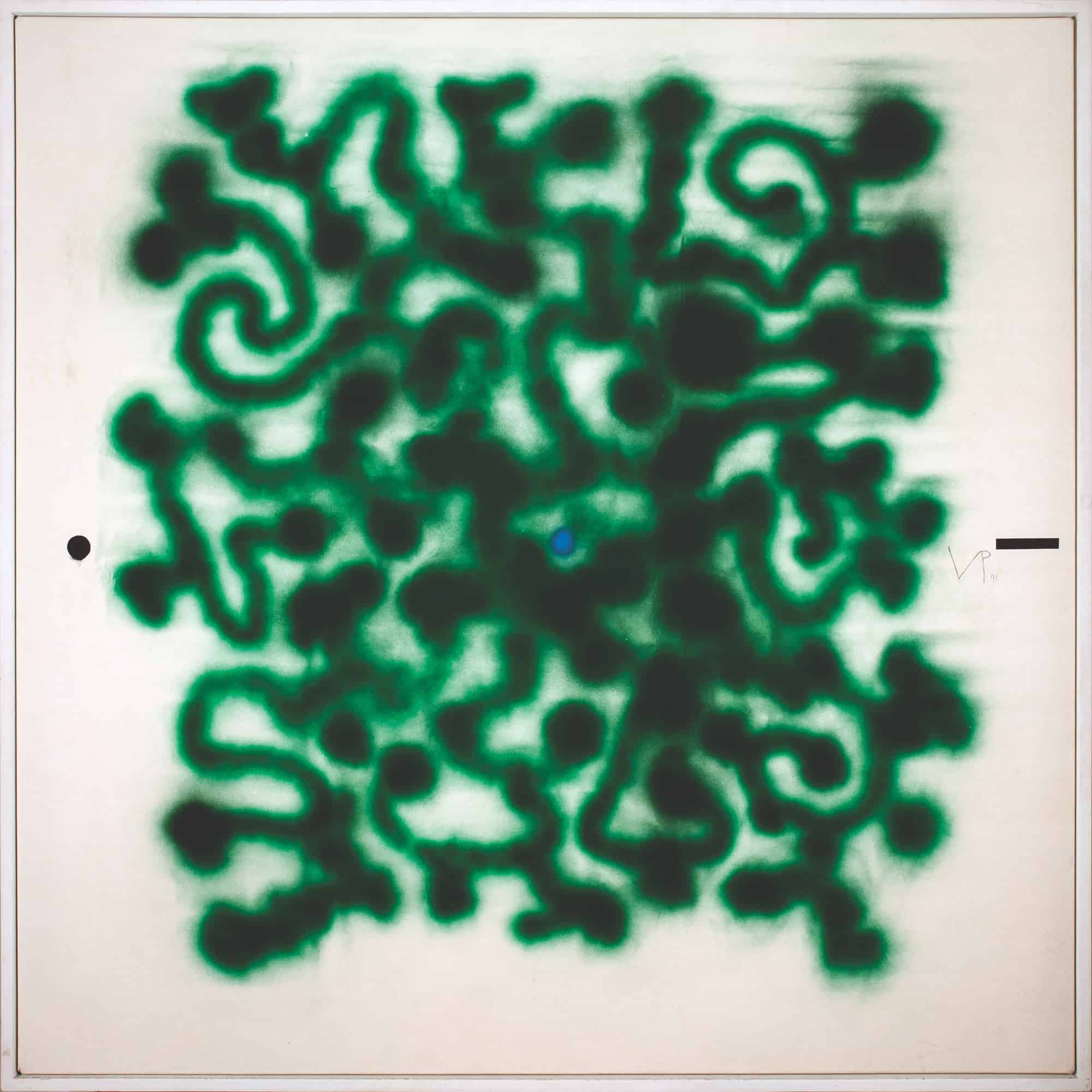

“In contrast to the measurable world of the Renaissance and classical science, the modern world presents a process of opposing forces, evolutionary developments and ambiguous relationships. Attempts to rationalise this in philosophy have been echoed in the abstract, conceptual and ambiguous imagery of modern art.”

Victor Pasmore, ‘The Artist’s Eye’, 1990.

“The artist makes a concrete object and gives it individuality. He creates a harmony parallel to that of nature and develops it according to a new and original logic.”