MEDITERRANEAN MUSIC

Antonia Critien

In my music I broke with most of what I had learned. I created a space in which I could accept new ideas ruled out by my training – Charles Camilleri (Mużiċisti mill-Qrib Lawrence Mizzi).

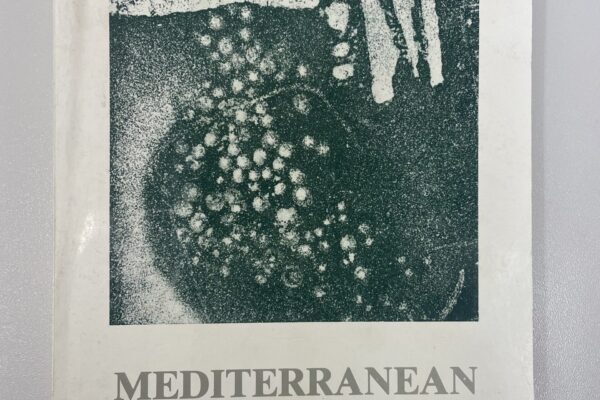

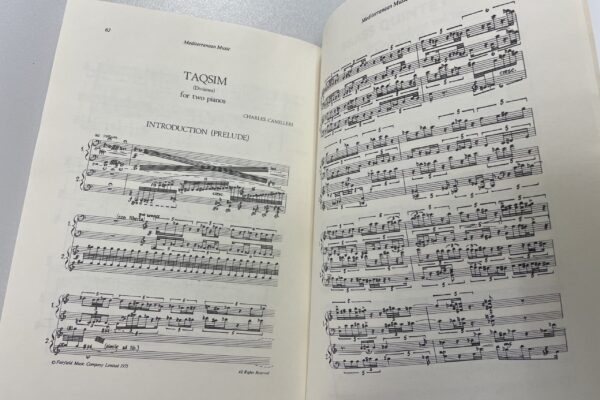

Maestro Charles Camilleri (1931-2009), Malta’s National Composer and one of international repute found his inspiration in local traditional music. This he researched and explored until it became a springboard for his own work, retaining the roots but reworking the melodies until he developed compositions that became more universal yet are instantly recognisable as his. The period from 1948 to 1954 saw Pasmore’s break into the abstract, and like Camilleri, he also had to cut ties with all he had learnt artistically so as to develop his unique style founded in abstraction. From around this time, he began to feel a strong music-painting connection, seeing the painter as composer and referring to abstract art as visual music. In the late 1960s, Camilleri devoted his time to researching the Afro-Arabic-European roots of Mediterranean music, composing pieces such as Taqsim (1965) and Maqam (1968), digging even deeper into the origins of Maltese traditional music. Having lived in Australia, Canada and the UK, in 1983 Camilleri felt it was time to settle back home in Malta. His permanent return to Malta in the mid-1980s came at a time of rising preoccupations with the soundscape of a region, in his case clearly the Mediterranean basin, and a composer’s ability to translate it into a meaningful musical language (Maltese Composers of Opera Joseph Vella Bondin). Mediterranean Music (1988), the publication that takes the form of a dialogue with Peter Serracino Inglott (his good friend and author of some of his opera libretti), was written soon after his homecoming, and brings together these deliberations, culminating in two operas in Maltese – Il-Wegħda and Il-Fidwa tal-Bdiewa. Victor Pasmore would make Malta his home in 1966, and despite never admitting to being influenced by his surroundings, his works from this era tell otherwise, mostly evident in the colours and textures he used. Still however, Pasmore stands true to a statement on abstract art he made at the time of one of his exhibitions, back in 1949 – In form it is neither illustrative nor representational in the literal sense of the word, but, like music, suggestive and evocative (Redfern Gallery Catalogue 1949). We know that Pasmore and Camilleri were acquainted. In the Victor Pasmore Archives from his home in Gudja, there is a typed note by Camilleri describing his work Morphogenesis which he had just completed in 1978. He considers this work as some sort of musical rebirth after years of ‘structural problems.’ The test of the artist he says is to organise his music or painting into a structure that is itself a springboard to other structures (Charles Camilleri– Aquilina and Saliba 1988).

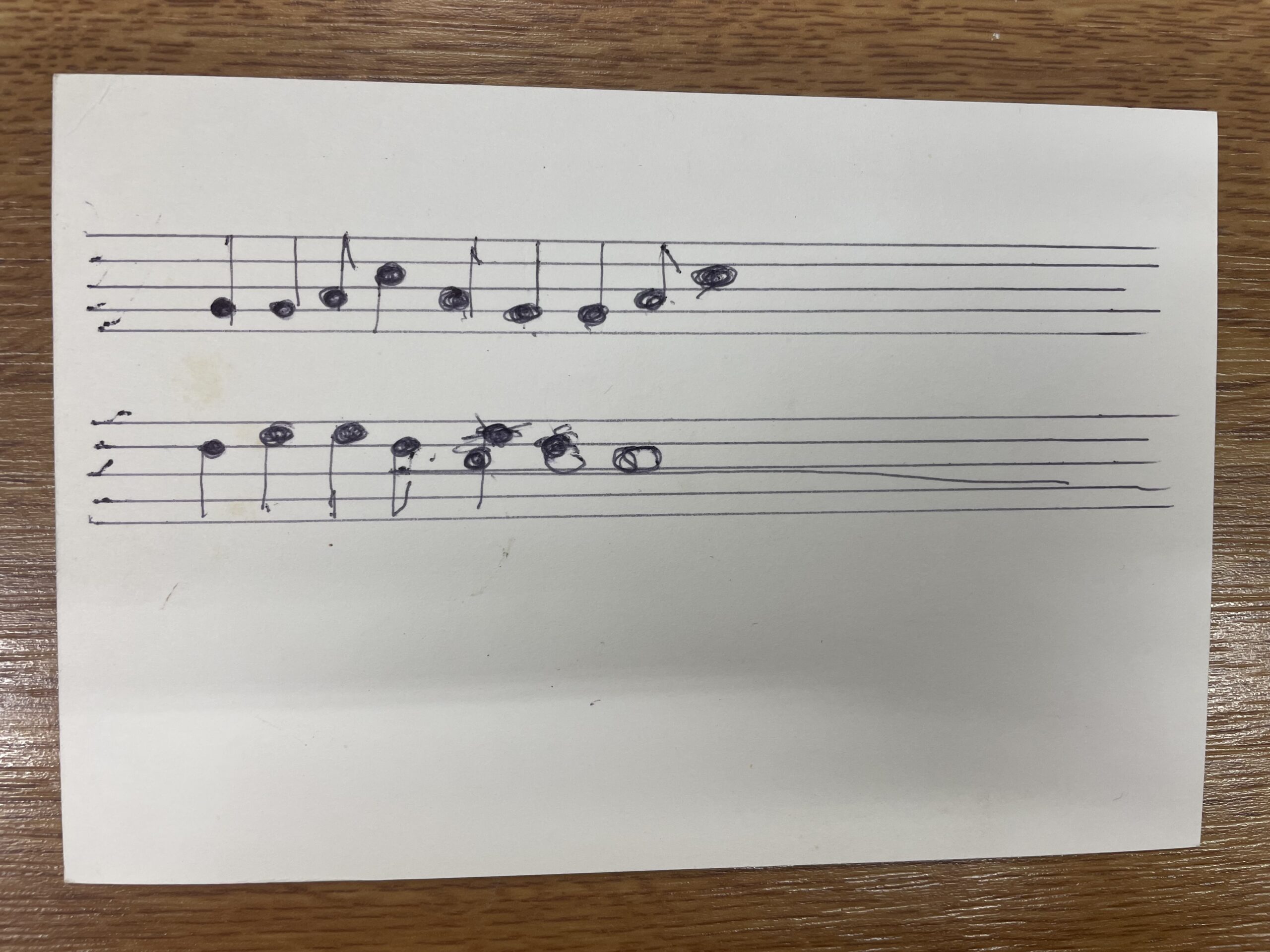

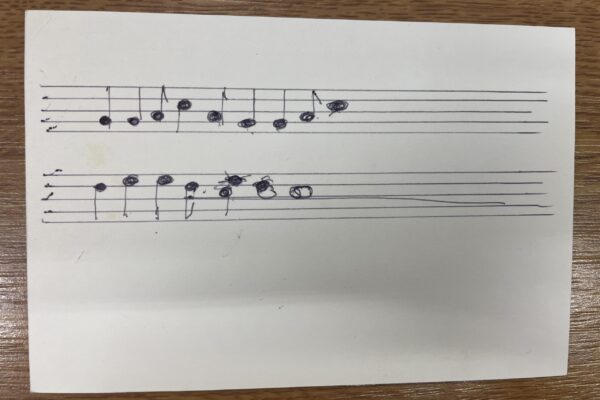

Inside the book is one of Pasmore’s personal note cards with his printed Gudja address and a musical doodle overleaf.

In 2018, Victor Pasmore’s children, John Henry Pasmore and Mary Ellen Nice, donated over 500 books and exhibition catalogues to the University of Malta, Archives and Rare Books Department. The Victor Pasmore Gallery is open to visitors at APS House, 274 St Paul Street, Valletta.