Self-discipline, pious spirituality and controversy pressed into one – Josef Kalleya is not only one of Malta’s Modern Art movement’s most important figures but one of the most impenetrable ones. While his art was at times controversial, Kalleya himself was anything but. The artist is known to have been incredibly modest and never sought to impress or impose.

Kalleya’s pieces give viewers the impression that they were pried, yanked or wrestled from the depths of the artist’s soul. His art is above and beyond, it is an ode to God, life and eternal forgiveness. He spent almost all of his life creating – sketching, sculpting, drawing, painting, developing and designing. It’s nearly as if his mission was to redeem his soul through artistic manifestation.

The Birth of a Pioneer

Understanding Kalleya does not merely entail knowing his work – the climate the artist grew up in had a strong effect on his creations. Giuseppe Calleja was born in Valletta on the 27th of March 1898 during British Colonial rule and at the height of Italian irredentism. The artist had to change his name several times to avoid confusion with other artists and actors who shared his name. He had a fairly normal childhood and was known to have a good singing voice – while he never received any formal musical training, Kalleya was a prodigious child – he could play the violin, guitar and piano by ear and composed melodic pieces regularly.

While the classical Ottocento style still had a firm grip on the local art scene, it was now steadily battled by the newly burgeoning British influences thrusting their roots in the country’s artistically insular climate.

Kalleya received a formal education at the Valletta Public School, St. Augustine’s and the Floriana Government School. As a child, he displayed an ingenious need for self-expression and formed part of a theatrical company named L’Avvenir Infantile. Josef enjoyed acting and singing in public – as a child, his performances were known to be melodramatic, spontaneous and favourably imaginative.

All Souls will be Forgiven

In 1913, when he was 15 years old, Kalleya experienced a life-altering episode which left a lifelong mark on him. Malta was celebrating the International Eucharistic Congress during which the Papal Legate visited the island. Kalleya was deeply affected by the experience of watching the Papal party disembark their ship. Within a few weeks, he encountered a young Dun Gorg Preca who greatly impressed the youth with his ascetic ideals. This prompted Kalleya to become a devoted member of the Societas Papidum Papidisarum (later known as M.U.S.E.U.M). It’s interesting to note that San Gorg Preca and his early devotees believed that matter blocked the vortex which spiralled man’s soul towards God – a notion we see in Kalleya’s later work.

Even though Kalleya formed part of the group for many years, his relationship with its members was somewhat uneasy. The sombre associates were the opposite of the spirited and creative Kalleya. The straw that broke the camel’s back may have been Kalleya’s exploration of different doctrines within the Catholic Church, this quickly alienated other members, as they felt it clashed with the group’s ethos. Eventually, through mutual consent and possibly trepidation, Kalleya left the group, nevertheless, he consistently harboured a high opinion of Dun Gorg Preca and retained good ties with the group.

During his exploration, the artist stumbled upon Origen’s doctrine of Universalism – a notable subject featured continually in his art. Origen’s doctrine of Universalism, also known as Apokatastasis, centres around the belief that when all things end, all souls, including the Devil, will be pardoned and reunited with God. While greatly frowned upon by the Catholic Church, this doctrine is seen and felt heavily when one gazes upon Kalleya’s work. A theme that swallowed his creations, engulfing them with a sense of deliverance, anguish and forgiveness through renunciation. His art and belief in Apokatastasis spoke a universal language which later on, his viewers resonated with.

Creation, Redemption, Salvation

During this time, the artist developed a love for drawing, painting and sculpture. Kalleya wanted to seek proper training, so in 1914 he began frequenting an art school run by sculptor Antonio Micallef. Eventually, he was also tutored by Giuseppe Calì, Edward Galea, Robert and Edward Caruana Dingli, Giuseppe Duca and Lazzaro Pisani.

Between 1916 and 1924 Kalleya found a job with Edward Galea, an interior decorator who employed him primarily to construct a range of stucco motifs, this was where Kalleya met sculptor Ignazio Cefai, whom he later apprenticed with. During this time, he began making a name through artistic commissions. The Neoclassical architect Andrea Vassallo hired Kalleya to produce two cherubs for the recently constructed Sanctuary of Ta’ Pinu in Gozo. It is said that the architect – who had a remarkably orthodox view of what cherubs should look like – was horrified beyond imagination when he laid eyes on Kalleya’s interpretation, and quickly shelved the project.

The artist travelled to Rome in 1926 to further his education along with fellow artist Oscar Testa, and within two years he enrolled at the Regia Scuola della Medaglia and the British Academy in Rome. By 1930 he was awarded a scholarship to study at the Regia Accademia di Belle Arti, he also attended classes on relief design and dye engraving.

In 1936, author Oreste Tencajoli wrote in his book Artisti Maltesi a Roma dal Secolo XVI ad Oggi, that Kalleya regularly visited major art centres in Italy whenever possible – it’s also notable that in his book Tencajoli dedicated most attention to Kalleya when reporting on the living subjects of his book. While in Italy, Kalleya and his peers Vincenzo Maria Pellegrini, Giuseppe Mangion, Carmelo Bonello and Vincent Apap funded the Società di Belle Arti.

Kalleya soon fell in love with Elsa Ornaro and asked his parents for permission to marry, but his father refused as Kalleya was a penniless student. The father conferred with Dun Alfred Gatt – a saintly visionary – who convinced him to give Josef his blessing, and on 7th July 1934 Kalleya and Elsa were married.

In 1935 Kalleya returned to Malta, where his career perked up and he was regularly commissioned to design stucco adornments for multiple structures including Villa Castelletti and Villa Apap. Kalleya transformed his Old Mint Street studio into a space where like-minded individuals could meet and share ideas. Together with Antonio Caruana, he ran a series of study sessions at the Studio Artistico Industriale Maltese d’Arte Sacra (Istituto di Cultura Artistica) which were attended by local artists Emvin Cremona, Giuseppe Arcidiacono, Vincent Apap, Giorgio Preca, Carmelo Borg Pisani, Esprit Barthet, Anton Inglott, Emanuel Borg Gauci and Willie Apap. The Old Mint Street studio was later transformed into the Libera Scuola del Nudo, subsidised by artist Lady Bonham Carter, the British Governor’s wife. It was the only place in Malta where artists could paint nude models live, rather than using plaster casts. The models hired by Kalleya were the well-known swimmer Turu Rizzo and a Hungarian ballet dancer.

As soon as the Church got word from the unhappy neighbours who labelled the classes as a whorehouse, they quickly shut it down as they were deemed reprobate for conservative Malta. During this time, the Curia also held special privileges to censor art exhibitions before their inauguration and vacate any nude art on display to avoid corrupting public morals.

Simplicity through Symbolism

By 1937, Josef Kalleya started working in Government Schools as a Drawing Master, his method when teaching art to children was to take a free approach which encouraged boundless creativity.

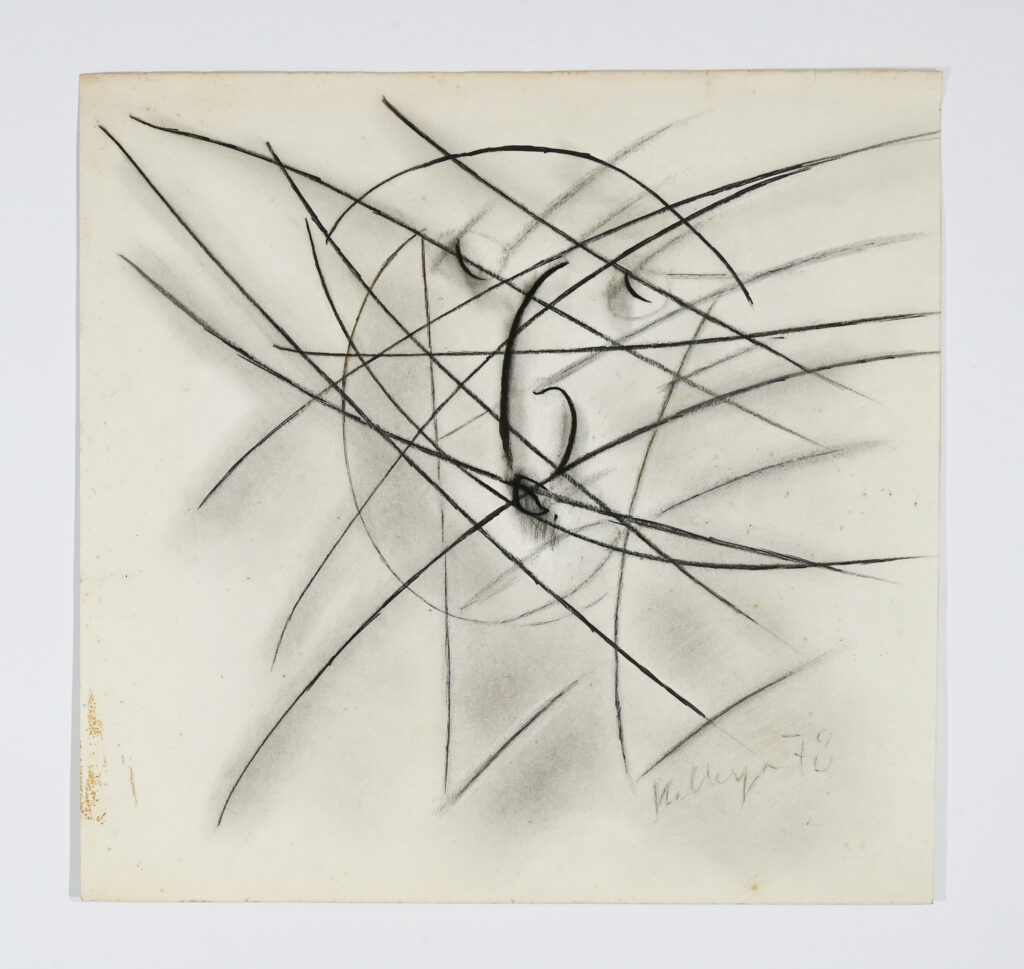

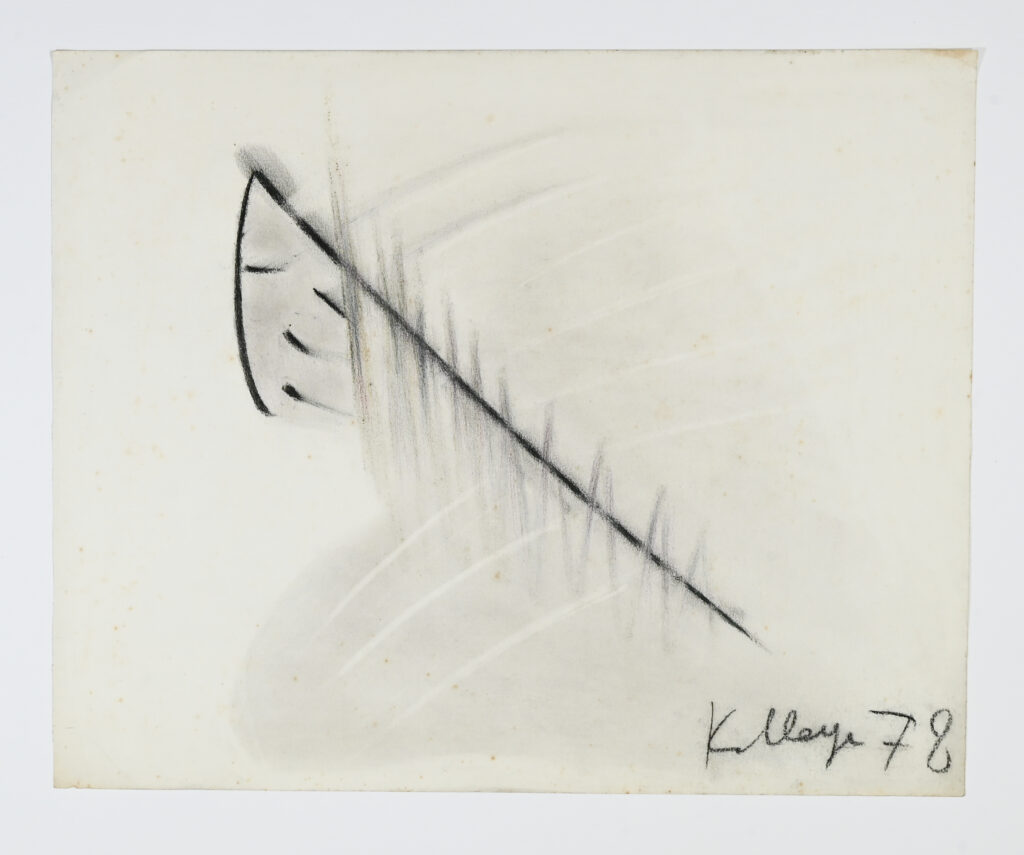

Kalleya’s artist work now started perching on a very narrow thread between the symbolic and the conceptual – his rebellious style was a far cry from the traditional works his contemporaries were creating. Through his tempestuous intensity and ability to infuse his works with emotional energy, the artist found ways of communicating directly with viewers through spartan and turbulent sculptures and drawings. Consecration through torment was a recurrent theme in Kalleya’s primordial art, a safe space where he could lay out any spiritual preoccupations through austere and symbolic creations.

He also adopted the habit of photographing his work and accompanying it with explanatory writings, particularly his more expansive compositions, which he aspired to one day see embellishing public spaces in Malta – a dream that sadly never materialised. It was also right around this time that Kalleya started producing his sculptures using plasticine – he photographed and destroyed them only to reuse the material to form new sculptures. On other occasions, he would leave the statues out to be ravaged by the elements, solidifying the need to convey his message that redemption is achieved through suffering.

In 1940 the Second World War broke out, disrupting the artist’s life drastically. He had to shift to different jobs to keep his family afloat and worked as both a watchman and an air-raid warner. Kalleyae was commissioned to work with fellow artist Marco Montebello to carve religious effigies in shelters for devotees to pray to. One example of these stone-cut effigies was made in the Misrah il-Barrieri shelter of Santa Venera – a large haunting Crucifixion scene emphasising suffering, heartache and despair.

Kalleya changed his name to Josef Kalleya in 1950, and in 1952 he co-founded the Modern Art Circle (later known as the Modern Art Group and eventually Atelier ’56) an instrumental group in promoting the Modern Art Movement in Malta. Atelier ‘56 later elected Kalleya as their president.

Creation as a means to Salvation

Kalleya retired from his teaching position in 1960, a decade which marked a new level of intensity in the artists’ work. While he was always studious, academically inclined and introspective, in the early 1960s he started experimenting with his newfound appreciation for La Divina Commedia by Dante Alighieri. During the subsequent years of his life, the artist produced over a thousand pieces centred around this narrative. Coincidentally Kalleya first read Dante in the same year that the Società Dante Alighieri, a society promoting Italian culture and language, was revived in Malta after an almost 20-year ban on pro-Italian activities.

Kalleya did not recontextualise, explore or remodel La Divina Commedia – he nabbed it and moulded it into his own experience and language. It is known that the artist read the book cover to cover countless times – while this may be looked at as nothing more than the fixation of an avid reader upon face value, one cannot help but notice numerous similarities between Dante and Kalleya – even though writer and reader lived hundreds of years apart. Dante used his verses as a means to salvation, just like Kalleya used his art for the same outcome.

Kalleya’s fixation with Dante’s work may be seen as an emphatic one which presented the artist with a deeper way of understanding and processing suffering. Both writer and reader were jaded by the political, ideological and theological situations they lived through – both artists struggled with the ecclesiastical idea and the bureaucratic structure of the Catholic church – an entity both artists struggled to be accepted by throughout their lives.

Kalleya was married to an Italian woman – they lived through the Second World War and during a time when Malta was rife with pro-imperialistic sentiments. This made it difficult for Kalleya to navigate through local scenes at times – tiptoeing the line between being accepted and looked at suspiciously within the local community. Another reason why he may have found solace in exiled Dante’s writings.

One can see other parities between Dante and Kalleya – both lived through a language question to their merit. Alighieri experienced a lingual struggle that pitted the classic Latin language, Greek and the newer Italian tongue. Kalleya experienced the language question in Malta, where the elitist Italian and new English were pitted against one another. Funnily enough, while Dante supported the use of the Italian language, most members of the Società Dante Alighieri favoured Italian being utilised as Malta’s official language, and not Maltese – much to Dante’s imagined chagrin.

One can notice a playful streak of this struggle in Kalleya’s written works, where Italian and Maltese spelling, grammar and punctuation are mashed into one. Given the high level of literacy and intelligence that Kalleya possessed, along with the endless tomes of not-so-light reading he is known to have indulged in, this can only be seen as an intentional display of connection between the two languages, rather than an honest oversight.

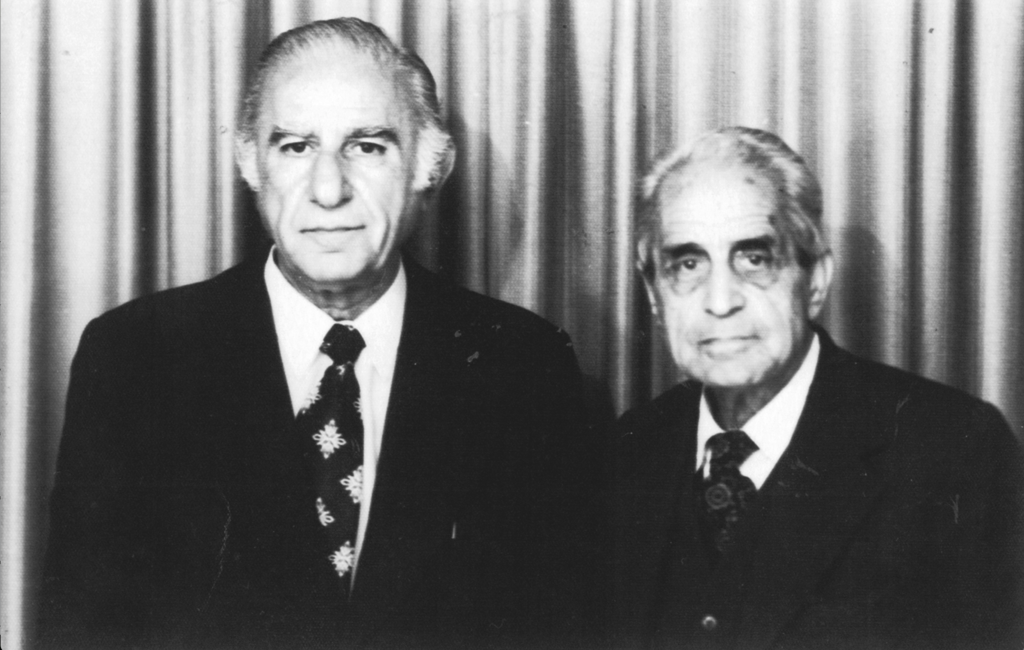

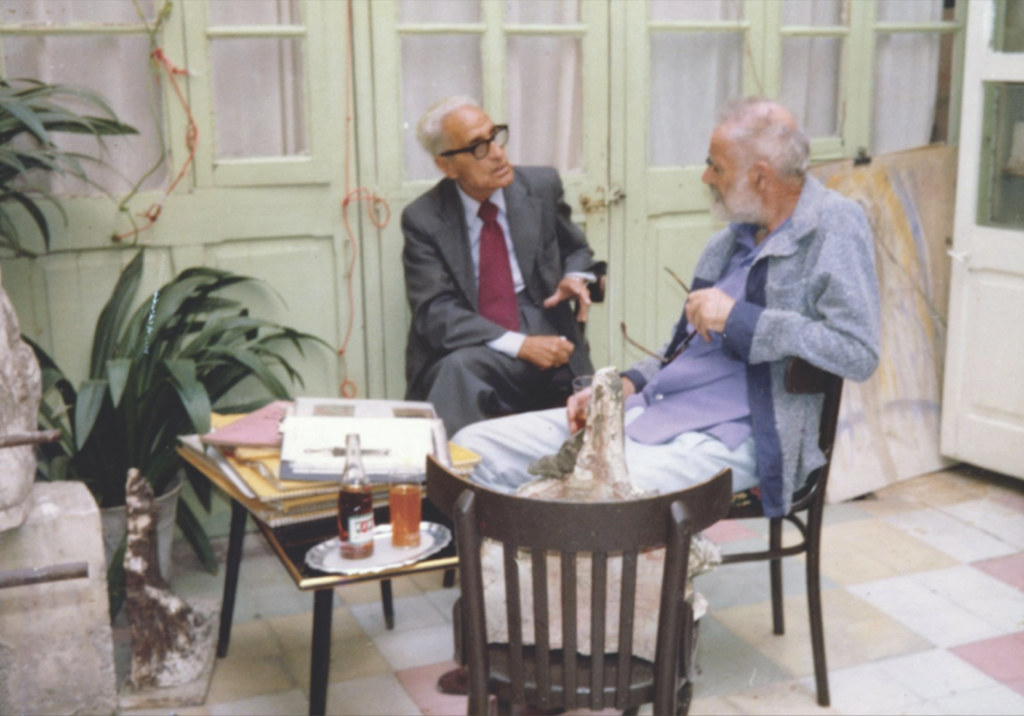

Kalleya and Pasmore

Victor Pasmore, a great admirer of Kalleya’s work, moved to Malta just a few years after the island gained independence in 1964. While the two never formed a tight friendship, they shared a close friend in common, Gabriel Caruana. Kalleya and Pasmore were not close, however, they both spoke a similar language – abstraction – a tool the two artists used to find meaning and redefine reality in a way they felt spoke to them. The two were known to have deep and lengthy intellectual discussions and held great respect for one another.

Josef Kalleya kept producing art until just a couple of weeks before he passed away at the ripe old age of 100, surrounded by his beloved family.

Kalleya had a prolific career during which he regularly exhibited his works. His most renowned exhibitions were the Sacred Art Exhibition at St John’s Co-Cathedral and his three solo exhibitions at the National Museum in Valletta, the Franciscan Friary and the Cathedral Museum. The veteran artist also led and gave practical support to the Vision ‘74 art group and partook in numerous exhibitions such as Ghajta Siekta and the 65th-anniversary MUT exhibition in 1984. Kalleya also won several accolades and medals for his notable works including the Midalja ghall-Ordni tar-Repubblika ta Malta and a gold medal from the Malta Society of Arts, Manufacturer and Commerce. Moreover, one of Kalleya’s prestigious pieces was gifted to Pope John Paul II during his pastoral visit to Malta. The artist was made a member of the National Order of Merit.

His art can be found in countless private collections and has been exhibited internationally, including in California, Moscow, Detroit, Rome, Denmark, Australia and Vatican City.

![[DETAIL] Pierrot, bronze, 1960s](https://victorpasmoregallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/B091392.jpg)

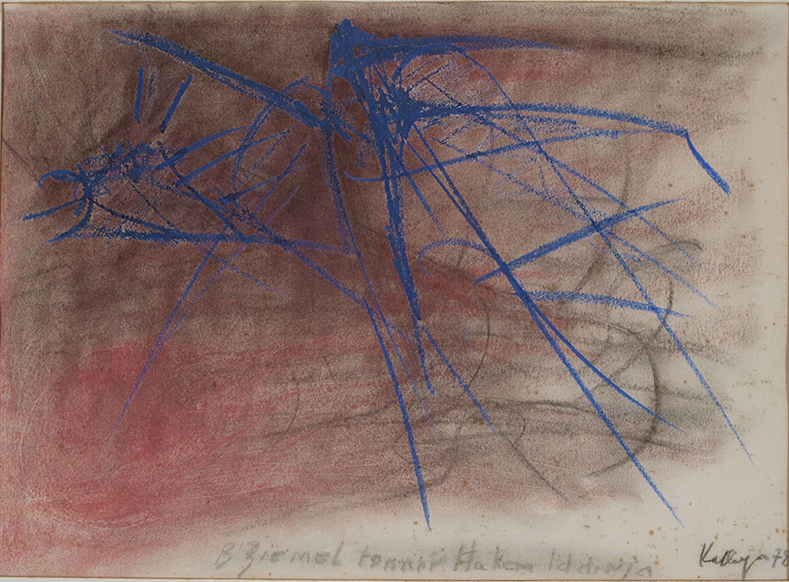

![[DETAIL] B'Żiemel tan-nar Ħakem id-dinja, coloured chalk, 1978](https://victorpasmoregallery.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/03/B091146.jpg)