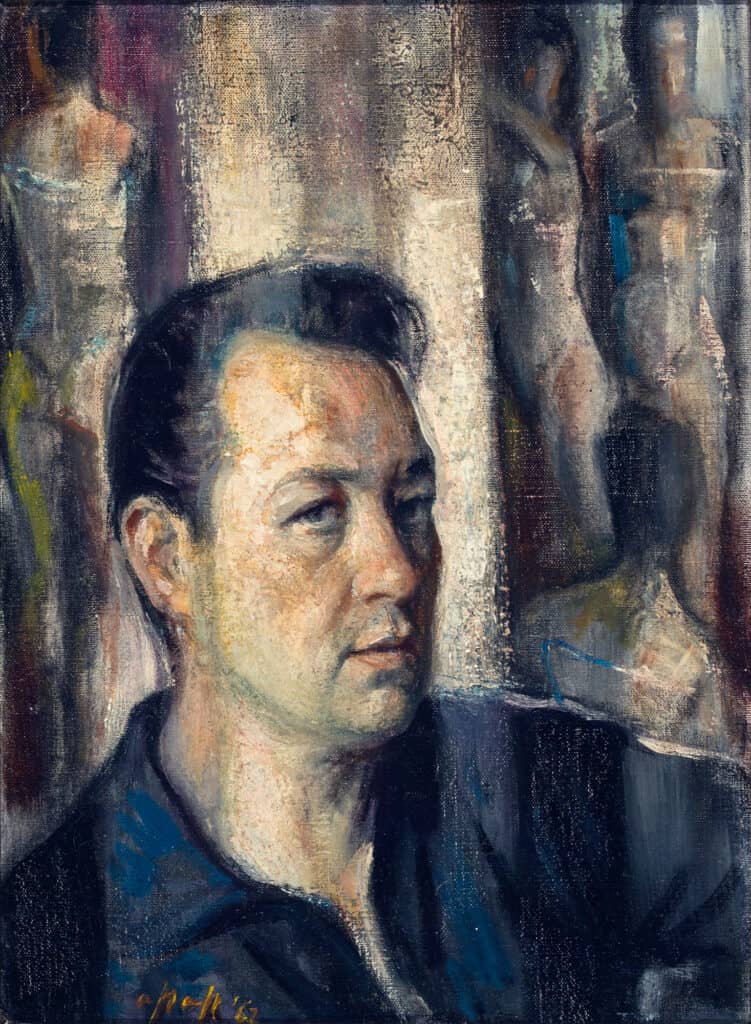

Willie Apap’s work inspects the human frame with a heavily penetrating contemplation — be it through his caricature-like figures, faceless nudes or religious depictions. He was known locally as a prolific portrait painter, an identity which for many years overshadowed his internationally acclaimed work, which showed a different side to his art. Apap’s forms drifted from highly whimsical ones in the early stages of his career, to ambiguously eyeless figures whose souls were dislodged from their bodies, only to be replaced with ink, charcoal or paint in his later years. For Apap, the human body was a tool created to perfect his artistic talents.

The Formative Years

Born on the 26th of June 1918 in Valletta, five months before the end of the First World War, Willie Apap was the son of Giovanni Apap and Marianne née Grimes. He was the youngest of five siblings, brother to acclaimed sculptor Vincent and musician Joseph Apap. Apap’s childhood was framed by difficult and unrestful circumstances, such as the Sette Giugno Riots, the 1921 Constitution and the Language Question. Malta was also on the brink of a great famine — military-based jobs were no longer required and the price of bread soared drastically. This brought about widespread unemployment, political unrest and mass emigration, all of which would not only shape the Maltese islands, but also Apap’s formative years.

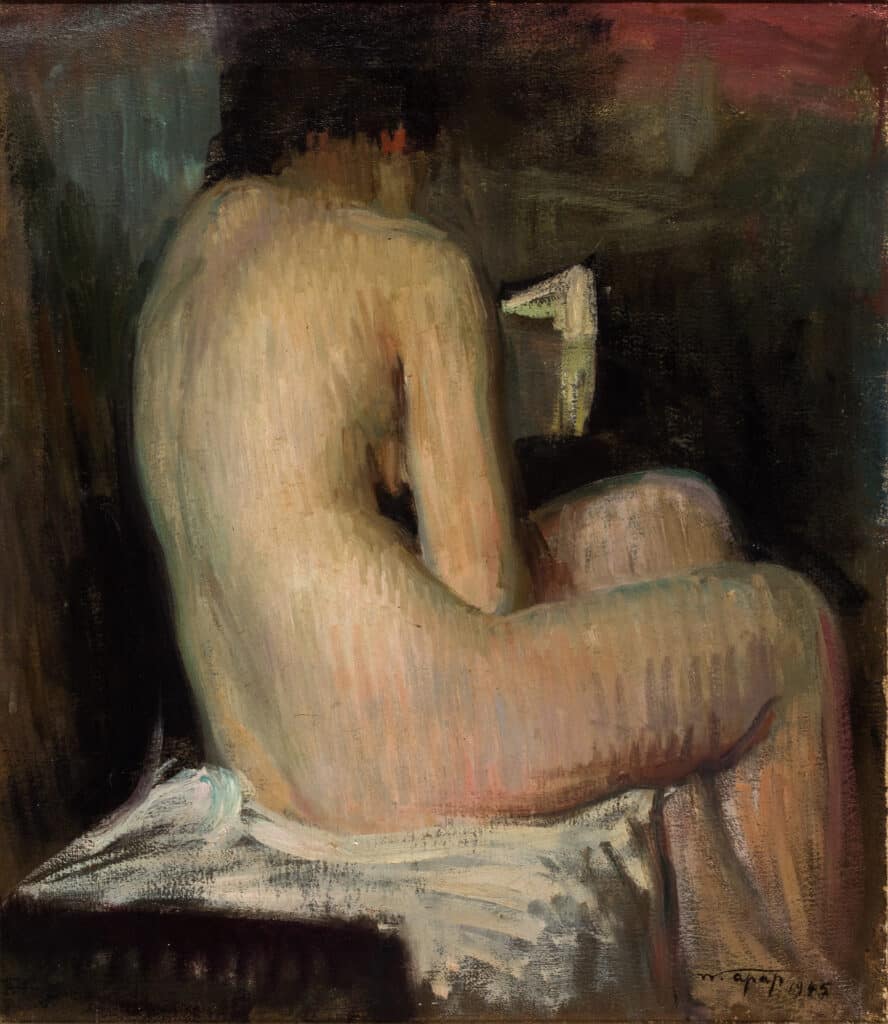

Willie Apap enrolled in the Government School of Art in 1933 at the age of 15, where he studied under the tutelage of Edward and Robert Caruana Dingli. During his studies he also formed lifelong friendships with his contemporaries Emvin Cremona, Victor Diacono, Anton Inglott and Esprit Barthet. Apap also attended private lessons under Josef Kalleya’s guidance, where he was given the liberty to paint nude figures – a practice which was heavily prohibited at the Government School of Art.

Hard work, talent and determination led to his first publicly viewed work, as the artist was engaged by his Italian teacher at the Lyceum, Arnaldo Fabriani, to illustrate a book titled Fiabe – Tradizioni – Leggende Maltesi, published in 1934. Fabriani later enlisted Willie to illustrate other booklets in the same series. While premature when compared to his later work, these drawings show the first etchings of the internationally acclaimed work Apap is known for. The animated movements of his caricatures showed ripeness for his age, and his sense of composition elevated some of these illustrations. When the yearly scholarship examinations approached in 1935, Willie Apap and Esprit Barthet requested permission from the Government School of Art’s director on behalf of their class to start attending school during the day for extra practice. Permission was granted, creating a healthy competition between these young artists, all vying for a scholarship grant at the Regia Academia di Belle Arti in Rome. By 1936, Apap was already taking part in group exhibitions, with his first being the Malta Art Amateur Association at the Auberge d’Italie in Valletta.

In 1937, Apap opened his first solo exhibition at the Caffe’ Premier in Queen’s Square, Valletta. This gave him excellent exposure, as the square was one of the most popular gathering spaces in the city — it was also close to the Casino Maltese, an elite club whose members came from the affluent strata of society, paving the way for Apap’s future commissioned work.

Apap was consistently practicing whenever possible, he was routinely spotted painting at San Anton, Sa Maison, Mosta and Birkirkara with fellow artists and friends Toussaint Busuttil and Giuseppe Arcidiacono. Moreover, he regularly painted at Caffe’ Premier with his friend Esprit Barthet after their evening classes.

Life in Rome

Willie Apap and his schoolmate Victor Diacono won a highly coveted scholarship in Rome to study at the Regia Academia di Belle Arti. One of the conditions imposed on the Maltese students reflected the strained fascist climate of Italy at the time— only those belonging to an Aryan race were eligible for the scholarship. Incidentally, their roommate happened to be the Maltese artist Carmelo Borg Pisani.

Apap was heavily influenced by the Neapolitan Ottocento, making his studies under Carlo Siviero particularly exciting for him. Siverio was severely prejudiced against Maltese students — an issue later resolved by a visit from Edward Caruana Dingli.

Willie’s time in Rome was meant to be an artistically unshackling and exploratory time, but in less than two years it turned into a discombobulated fever dream thanks to the Second World War. Apap’s family implored him to head back to Malta like his peers in Italy, but Siverio, not wanting to lose one of his star pupils, wrote to Willie’s brother Vincent, urging him to convince his family to let Willie stay in Rome to further his studies. While this decision proved to be a paramount milestone in his artistic career, Apap was now considered a traitor and an Italian iridescent by the British Government during a particularly tempestuous climate. That same year 120 Maltese men were apprehended and interned by the British for ‘security measures’.

Apap was eventually approached by Giuseppe Biscottini, head of the Comitato d’Azione Maltese and convinced to give up his British passport in exchange for residence and an Italian work permit. Not wanting to lose the golden opportunity to study in the Eternal City, Apap agreed. While this might imply that Apap was swayed by fascist ideology, it was not the case, as later stated by his dear friend Victor Diacono many years later: “Once, me and Willie were returning home late at night […] and we passed through Piazza Venezia where the Duce used to have his mass-meetings and speak from the balcony. Well, we calculated exactly the precise centre of the square then, resting back-to-back and supporting each other, we pissed on their Fascism!”

In 1940 Apap was commissioned by Biscottini to paint a portrait of King Vittorio Emmanuele III of Italy. Reluctantly Apap accepted, and at Biscottini’s insistence, used the Grand Harbour as the background for this painting. A hefty sum was paid for the work, but still not a fair one considering the grief this painting would cause Apap. By 1943 Willie obtained a Diploma di Licenzia, and moved to Buccino, as the situation in Rome was deteriorating at lightning speed. However, within just a year, the struggling artist returned to the city where he managed to survive the war and exhibit poorly received and heavily criticised landscape paintings.

The Blacklist

Apap’s time in Rome came to an end following the Allied invasion of Italy in 1943, during which he gave himself up to the Irish Fusiliers. He later joined the group as an interpreter as he was fluent in both English and Italian. By this time, Apap most probably unknowingly, formed part of a Maltese renegades blacklist formed by the Malta Police Force, possibly supplied by none other than Carmelo Borg Pisani during interrogation. He was eventually arrested and held at a detention camp in Naples where he spent his time in captivity drawing, sketching, painting and etching on whichever surface he could get his hands on, using his fellow inmates as his newfound inspiration. The war ended in 1945, the same year that Apap’s dear friend and fellow artist Anton Inglott passed away.

Apap delved into the world of caricatures, one of which survives to this day. While sitting for a group drawing, one of the inmates jokingly made a blistering sign behind another’s back — a gesture which Apap mirthfully captured in his illustration. The unfortunate victim of this now-immortalised gesture was so offended that upon seeing the distress it caused, Apap tore it up to avoid further conflict. Luckily, one of the detainees saved the pieces and reassembled them, making the picture a priceless fragment of Maltese history – the only existing depiction of the Maltese prisoners together.

Eventually, the detainees were deported to Malta and imprisoned at Corradino Prison in Paola, where they had to sit for trial on the 7th of January 1947. One of the Corradino prison guards later stated that Apap once broke a terracotta bowl to use as pigment for a portrait of his mother depicted as the Virgin Mary, an image that is said to have brought solace to Apap and his fellow inmates.

The Conspiracy Trial

Apap and his peers were tried for treason in 1947, during his sittings he created the acclaimed Conspiracy Trial Drawings, marking a newfound maturity in Apap when compared to his previous works. The treason charges included the men becoming members of the Comitato d’Azione Maltese when Italy was at war with Britain and of conspiring to overthrow the British Government in Malta by assisting its enemies.

Incidentally, this was also around the same time when the phrase ‘biskuttini f’ħalq il-ħmir’ was coined, referring to the heavily debased defendants. These young men were humiliated upon their return to Malta for giving up their British passport in exchange for an Italian one — the group was referred to as ħmir f’ħalq Biscottini, alluding to Giuseppe Biscottini who convinced them to do so.

Apap, ever disinterested in the hearing and engulfed by his need to create, repeatedly explained that all he wanted to do was paint. The artist insisted that he only took Biscottini’s offer because his British Government Scholarship would come to an abrupt end, forcing him to accept a grant from the Regia Deputazione per la Store di Malta to keep studying at the Academia. His defence lawyer, Dr Giovanni Filiberto Gouder claimed that some of Willie’s actions were enforced by the school, such as this attendance at the unveiling of Fortunato Mizzi’s bust at the Pincio Gardens. It was also stated that the background in King Vittorio Emmanuele III’s portrait was done to depict the King as a Grand Prior to the Knights of St John. During the trial it was also brought to light that Carmelo Borg Pisani and Willie Apap had been estranged from one another for quite some time.

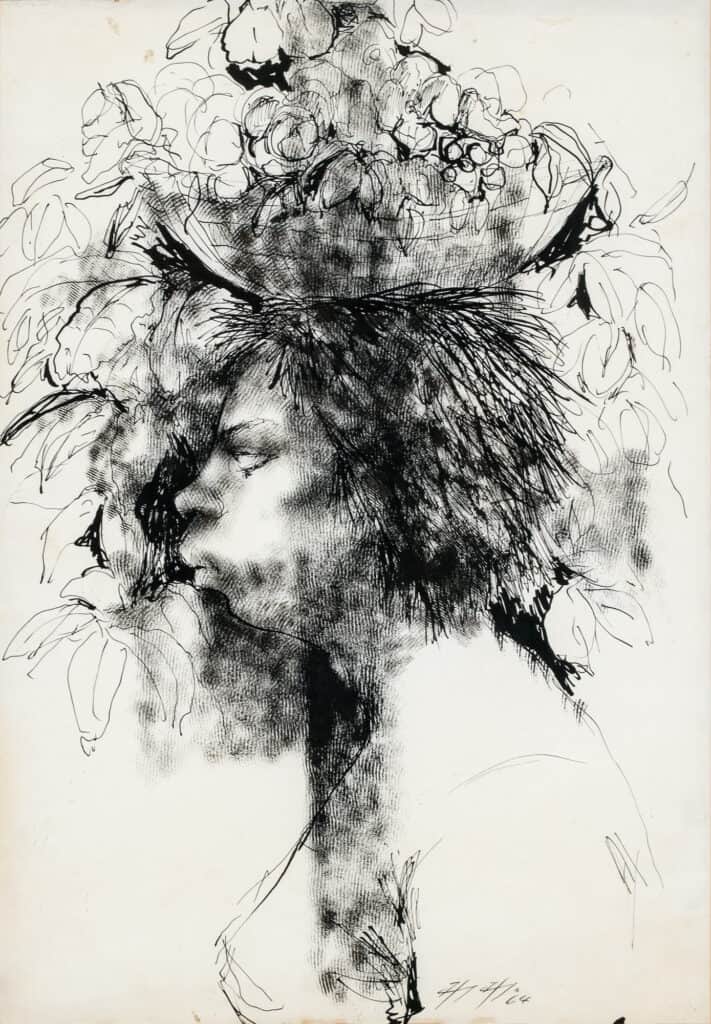

Many years later, Dr Gouder observed that at the beginning of the trial Apap would draw on any piece of paper he could get his hands on. The lawyer quikcly understood that there was no way of forcing Apap to pay attention to his own trial, so he bought the artist a sketchbook to keep him occupied. This gesture marked the beginning of the Conspiracy Trial Drawings — a collection of beautiful sketches that show dexterity, talent and delicate movements. Strokes of varying thickness, smudged and purposefully faded lines, agile and velvety marks displayed a new side to Apap, one that contrasted greatly from the Neopolitan Ottocento style he was so fond of back in Italy. It almost seems like the painter went back to his roots during this trial, forever leaving behind the Ottocento approach.

The jurors took a liking to Apap – his whimsical designs were far more entertaining than the trial itself, Dr Gouder claimed that he would catch the jury looking over Apap’s shoulders, with Willie even occasionally holding up his sketchbook for them to admire. Apap’s creations during the trial varied from comical caricatures to lifelike creations, they also spoke volumes to the jury — far louder than the accusations brought forward against him and his peers, and it soon became quite obvious that the jury had no intention of condemning such a gracefully-natured creature to the gallows.

Apap was found not guilty on all counts; however, the whole experience clearly scarred him – from the war itself to Inglott’s death and the trial, these bitter experiences left a scathing mark on the artist and his work. Apap imbued himself in the creation of portraits and religious paintings, undoubtedly, this commissioned work was needed for him to survive the post-war period. His creations now reflected the harshness he experienced in fascist Italy – his quasi-dystopian work had a futuristic coldness to it, contrasting greatly to the Baroque creations his insular Maltese contemporaries were creating. The artist matured rapidly and drastically, his works now became intense, sombre, expressive and charged with a tempestuously poignant rumination that made use of harsh lights and engulfing shades.

Return to Rome

By 1955 Apap made his way to Rome and set up a studio in via del Babuino, hook part in his first post-war collective exhibition at Palazzo Venezia and made the city the heart of his artistic activities. It was around this time that we see the introduction of his distinguished strisce, reminiscent of light flowing through a prison cell’s barred windows. In a way these strisce provided a sense of solace and comfort for the otherwise sad and ever-increasingly desolate figures Apap was now depicting. An added bitterness made its way into his work, remindful of hardships and loneliness, comforted only by the presence of the strisce – rays of celestial redemption reminding his crushed subjects that salvation is near.

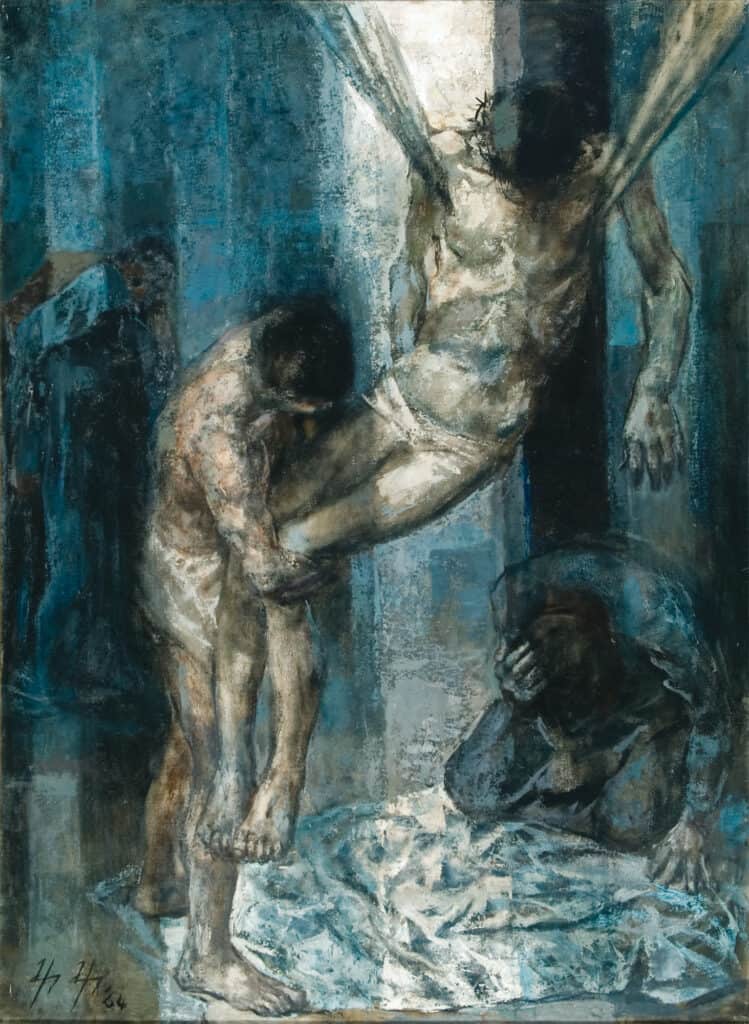

The Sixties were a busy time for Apap who joined his brother Vincent at the Commonwealth Institute in London for a joint exhibition, after which he was invited to Windsor Castle to paint Princess Anne’s portrait. Apap returned to Rome shortly thereafter, where his artistic recognition within the religious stratosphere reached new heights in 1964 with his critically acclaimed oil painting ‘Descent from the Cross’. That same year, the artist won first prize for painting at the Mostra d’Arte Sacra in Celano and travelled to Brazil, where he stayed at the favelas in Rio de Janeiro.

Within the favelas Apap found ample subjects to draw and sketch, with his favourite being those whose identity he could shape in whichever way he pleased – his feverish strokes painted many faceless, eyeless and unknown women who manifested his exploration of metaphysical and spatial philosophies, like his Italian contemporaries Tato, David Grazioso and Renato Bussi.

An Artistic Transformation

Apap’s work now exhibited a steady transmutation from holy effigies to obscure, eyeless and mysterious portraits draped in heavy strokes. The nude female figure was now one of his most depicted subjects – never sexual or provocative, but devoid in character. Ballerinas were another subject Apap was fond of, not in movement, but in repose – always faceless, still and silent. The women Apap painted served as vessels for his reflections, almost always carrying a sense of deafening silence.

Dramatically dense and simultaneously striking, Apap’s later work can attract and repel at the same time — suffering, serenity, heaviness, rest, pain and stillness can all be noted in one piece. The multidimensional strokes, liberating light and engulfing shades all fused together represent the many faces of Apap himself — from a prolific and complex painter of sacred art to one that portrays hauntingly heavy flesh and unending suffering. It is interesting to note that later, Apap adopted the same hauntingly pronounced fragility in his religious paintings, where his holy subjects are almost always depicted as being swallowed by pious suffering and self-sacrifice. Apap’s subject towards the end of his life seemed to be weighed down by the reality of their own emotions, torn apart, dissected and divided by grief, sorrow and woe. During this time, Apap exhibited his work in Argentina, England and Sweden, becoming a painter of international repute. He made a complete transition from commissioned portraiture of the Maltese elite to Church altarpieces in Rome, and in 1965 he was hired to paint the altarpiece of Santa Rita for the church of St Peter at Terni.

Apap passed away on the 3rd of February 1970 at the age of 51, in his brother Vincent’s arms in Rome.

A Legacy Like No Other

Several posthumous exhibitions honouring his work took place in Malta and Italy, and a commemoration in his honour took place in Floriana in 1972. In 1990, His Holiness Pope John Paul II was presented with Willie Apap’s ‘Miracle of the Viper’ painting as a gift upon his visit to Malta. Apap’s work can be admired in numerous collections, both public and private, all over the world.

Apap’s harrowing art is forever cemented in Malta’s artistic history, his distinctive style and ability to present the human form like no other has made Apap’s contribution praised in international artistic circles.

His work should be viewed in light of what Europe was going through at the time, and not solely within the local context. While his Maltese contemporaries suffered through war, Apap experienced first-hand the brunt fascism in Rome. He braved the tide and followed his call to create even when it was close to impossible to do so, in turn making his impact on his Maltese peers difficult to ignore. His presence was crucial in the local art scene as it cracked open the heavy insularity and British influences the island was facing at the time.