Daring hues, futuristically stylised figures, assertive compositions and geometric figures often characterise Emvin Cremona’s eclectic work – his versatility is unequivocal. His work’s synthesis, balance and directness enchant viewers to this day. Known for tactile reliefs, experimental abstractions and his eclectic mix of Constructivist, Futurist and Byzantine church commissions, Emanuel Vincent (Emvin) Cremona was one of the pioneers of the Maltese modern art movement.

The Formative Years

Emvin Cremona was a multifaceted and manifold artist who showed skill in design, with some of his most notable works including the Nadur Parish church altar and the interior design of the Ħamrun Parish church. Cremona was a prolific artist whose work adorns many of Malta’s churches, brought international attention to local stamp design for over three decades and had an incredible prowess for design and architecture.

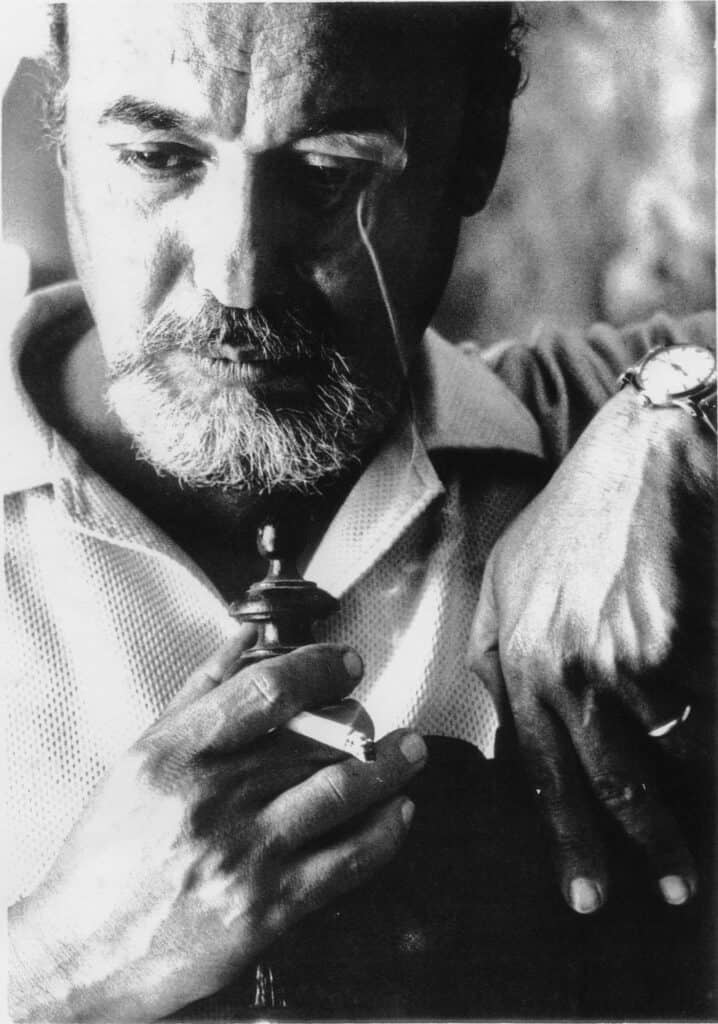

Cremona was born in Valletta on the 27th of May 1919. He discovered his love of art at the age of seven through a paintbox he received as a gift with which he spent hours painting as a child. Cremona was distinctively creative and even excelled in violin studies, however, no other member of his family was artistically oriented, making it difficult for him to get the encouragement and support needed to become a full-time artist. His father, Joseph, was particularly against Cremona’s artistic aspirations, but this mattered little, as he worked overseas for around 14 years, allowing Cremona to focus on his vocation.

The Artist formally began his artistic studies in 1935, when he enrolled at the Malta Government School of Art. There he studied under the tutelage of Carmelo Mangion and Edward Caruana Dingli. A year later he applied for a course at the Italian-funded Istituto Umberto I. Notably, at the time, Malta was home to extreme tension over the Language Question; while the English language was made official in 1934, Italian remained the main language at the Italian-funded institute. That same year, Italy swore allegiance to Nazi Germany, and many pro-Italian Maltese civil servants were dismissed from their jobs. Cremona recalled joining a Fascist youth organisation at the time — a common alliance for artistically inclined youths, particularly those who aspired to study abroad. Cremona was sent on a study trip to Rome, joined by fellow students Willie Apap, Esprit Barthet, Victor Diacono and Anton Inglott, with who he formed an extremely close friendship. In 1936, Cremona briefly attended Josef Kalleya’s La Scuola del Nudo and was introduced to design and printing through the master of modern etching, Carmelo Mangion.

Emvin placed third after Willie Apap and Anton Inglott in the 1937 Regia Accademia di Belle Arti scholarship exam. This did not stop him from pursuing his art studies; he managed to gather the funds to pay for his enrolment at the prestigious school. Cremona showed so much prowess that he won the Italian Government Scholarship for his second year of studies and second prize in a competition for the Overseas Journal of Education cover design. Within a year, he was registered in a pre-military course at the Malta-based Regia Scuola Umberto I, but requested to forgo this course to continue his studies at the Accademia di Belle Arti. That same year he had his first solo exhibition at the Ellis Studio in Valletta, and a joint exhibition with fellow Maltese students, most notably Carmelo Borg Pisani, at the Prelittoriali d’Arte. While studying at the Regia, Cremona became familiar with the works of Mario Sironi — an influence which lasted throughout the 1950s.

Tumultuous Years

One needs to acknowledge the strange climate in which Cremona and fellow artists found themselves — Rome in 1939 was under Mossolini’s Fascist regime; this meant that the Maltese students had to take oaths professing the Roman Catholic religion or stating that they did not belong in any way to the Jewish race. This was an abasing and needless conformity which had to be signed by the likes of Victor Diacono, Willie Apap and Anton Inglott, too, due to the Leggi Razziali (Racial Laws) of 1938. These laws affected Maltese students and workers, especially those of Jewish descent. Cremona was very much aware of the suffocating influence the Fascist regime had over the arts and culture — something which, while he abhorred, he had to adhere to so as to keep himself under the radar. This practice was adopted by most Maltese artists studying in Rome at the time.

The artist formed a deeper bond with Anton Inglott in Rome, with whom he shared lodgings and painted frequently. Against their parents’ supplications, the two stayed in Rome until just before Italy entered the war. Inglott and Cremona are said to have returned to Malta on the last boat to reach the Maltese islands before the war broke out.

Return to Malta

Emvin Cremona was enlisted with the Royal Engineers where his team leader soon noticed his artistic prowess. Cremona and Inglott — who conscripted together — were assigned to design camouflages for gun emplacements around Malta. Cremona was also entrusted with the restoration of the heraldic emblems at the Main Guard in Palace Square, Valletta. These activities helped local artists to not only feel like they could fit in but also gave them a sense of normalcy. Cremona served in the army for a total of four years, during which he provided work for ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association), an entertainment division of the Navy, Army and Air Force Institutes (NAAFI) in charge of recreation and entertainment for locally stationed servicemen.

At the height of the war, Cremona showcased his work in an exhibition organised by the Malta Art Amateur Association at the Palace Armoury, Valletta, followed by a solo exhibition at the British Institute, in 1943. Cremona won the Agnes Schembri Bequest Award, which aided him in furthering his studies at the Slade School of Fine Arts and the Ècole Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, in Paris. It is speculated that while in France, Cremona came across Jean Fautrier’s work and spent much of his time with Professor Jean Théodore Dupas — evident through the hint of Tachisme in Cremona’s works from the time.

In 1945, Anton Inglott passed away, marking a gargantuan loss not only for the Maltese Modern Art movement but also for Cremona. The anguished artist was chosen to pick Inglott’s metaphorical brushes and carry his unfinished work at the Msida Parish Church. Cremona was chosen due to his closeness to Inglott and his knowledge of the late artist’s conceptual aesthetics — the work of the two merged perfectly, delivering a seamless marriage of synthesis and respite. While this project may have aided Cremona in dealing with his grief, it also helped him develop a new style as if emerging from a cocoon. Cremona’s birth as a distinct artist who reminisced Byzantine art in his works ensued. Rich hues, beautiful gold leaf and archaic imagery were adopted in an otherwise modern context. Cremona found the perfect recipe; he was the perfect compromise the Curia yearned for.

A Union of Tradition and Modernity

The artistic advisor to the Curia, Vincenzo Bonello, was a strong admirer of his, which is why, to this day, Cremona’s work adorns many parish churches and collections all over Malta and Gozo. Cremona was commissioned to complete the Ta’ Pinu mosaics which were at first entrusted to Giuseppe Briffa. His first-ever application of gold leaf can be found in a delicate bozzetto of the Annunciation kept safely within the Gozitan Żebbuġ Parish church’s private collection. This overload of church commissions was a blessing and while they gave him a steady income to support his family, they also robbed him of his creative time and artistic spontaneity.

In 1948, Cremona became a tutor at the Malta School of Art and married Lilian Gatt, with whom he fathered four children. The family lived in a Valletta townhouse overlooking the Grand Harbour and the Ta’ Liesse church. Emvin opted for a home-based art studio from which he could work while being around his family. His studio was spread over two floors, with the living quarters serving as an extension to his studio and for his work.

He soon joined other artists and started demonstrating his ideas to the masses through carnival floats and designs — one of the few restriction-free platforms local artists had. Within a year, Cremona was commissioned to redecorate the war-damaged Knights’ Hall in Valletta, which at the time functioned as a theatre. He engaged some of his students to help out on this prestigious project, including Helen Vavagna, Tony Pace, Louis Wirth and Joseph Caruana. When Edward Caruana Dingli passed away, in 1950, Emvin Cremona replaced him as Master of Painting at the Malta Government School of Art. During this venture, he created a flexible studies programme and encouraged his students to partake in the carnival festivities. Some of his most notable pupils included Antoine Camilleri, Frank Portelli, Saviour Casabene and Alfred Chircop.

At this time, Cremona’s artistic style was heavily influenced by the Italian artists he admired, and his style was reminiscent of the Italian Aeropittura movement.

In 1952, the Malta Society of Arts, Manufactures and Commerce celebrated its 100th anniversary with an exhibition at Palazzo De La Salle, in Valletta. This exhibition was considered a landmark event in Maltese art history since World War II, as over 200 works were displayed and it included a wide range of works, from silverwork to models. One critic, writing under the pseudonym Phidias-Apelle, offered a mixed review of Cremona’s work. While praising his earlier and more traditional style, the critic found Cremona’s newer pieces to be experimental and lacking in direction:

Emvin Cremona left us perplexed; next to his sweet style of the past, a powerful portrait of Canonico there is a series of paintings that want to be a standout note and are instead attempts still very far from the goal. It is clear that Cremona has not yet found himself but it is time for him to seriously divide the path he wants to follow. We advise him to be in harmony with his own “self” without poses and vain experiments.

Cremona submitted three proposals for a public competition to design a fountain in Valletta. The competition was won by Vincent Apap with his iconic Tritons design. Cremona’s most acclaimed design for the fountain reflected his earlier experiences in Rome — it featured a tall pylon adorned with stylised figures depicting the history of Valletta from the arrival of the Knights of St John to its reconstruction after World War II, inspired by a pre-war project by the Italian artist Mario Sironi.

In an article published in The Times of Malta, an art critic remarked that most of the entries were ‘badly designed, antiquated in outlook, and doubtful taste’, except for one design, signed with the pseudonym ‘Ars’, which was misplaced for being impractical. The critic was unaware that this was Emvin Cremona, who addressed this issue in a published letter, questioning why the critic presumed that his submission was unplaced for the reasons mentioned. Cremona clarified that his artistic vision aimed to create a fountain that would stand as a monument, even without water.

Philatelic Designs and Abstract Creations

1957 marked the 15th anniversary of the George Cross Award and the year that Cremona entered the world of philately. He collaborated with the Malta Post Office during what is today known as the golden age of stamp design in Malta, as he created over 170 stamp designs for 62 different sets. Stamp design was naturally less strict, this presented Cremona with a creative outlet which the Church did not, resulting in modern designs. Another freeing outlet Cremona had at the time was stage design, as he created backdrops for two operas, La Predestinata, in 1955 and L’Araldo di Cristo, in 1960.

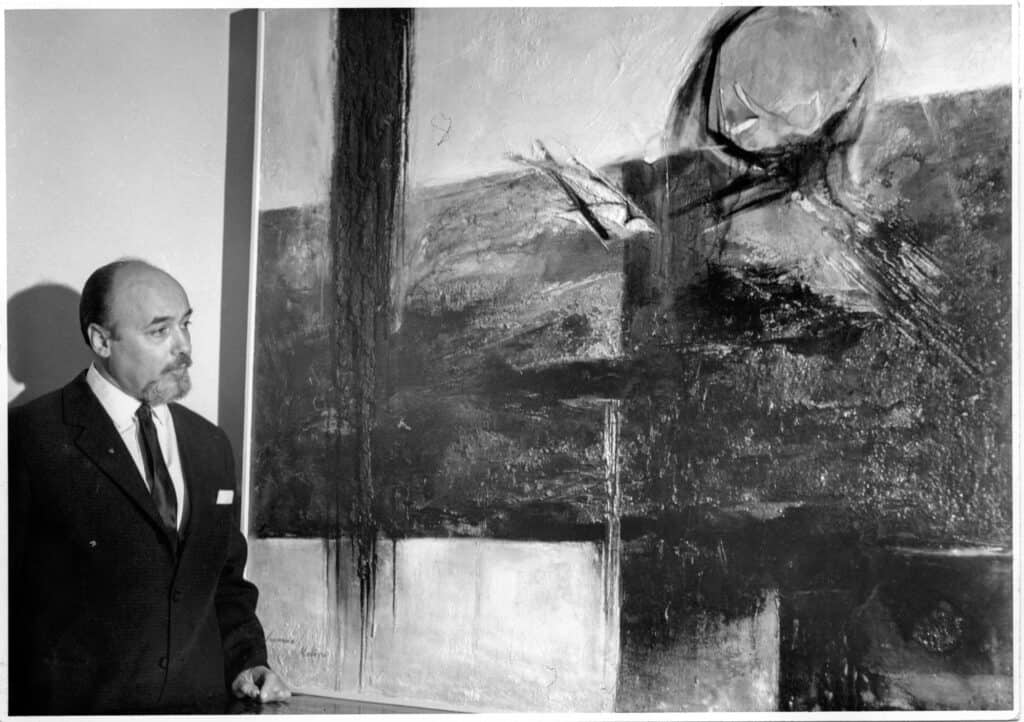

Emvin Cremona started experimenting with abstract art, a form which was not adequately comprehended locally or particularly liked by the local Church authorities. He also never joined the Modern Art Circle since he depended on canonical commissions to support his family. However, this did not stop him from exhibiting his work at the Venice Art Biennale of 1958, with Antoine Camilleri, Hugo Carbonaro, Frank Portelli, Carmelo Mangion, Oliver Agius, and Josef Kalleya. The works presented by Cremona were the only abstract ones the Maltese team exhibited. Cremona’s works depicted a spatial explosion of sorts, his viewers were slammed with a search for order in chaos — a disarranged arrangement that confounded but brought a pleasant balance.

It was at this Biennale that Cremona came across the works of fellow exhibitor Alberto Burri, which inspired him to experiment with different textures like fabric, sand and gravel. He started painting over unprimed canvases and experimenting with his colour palette.

In 1959, Cremona started working full-time with the Philatelic Bureau and was at an all-time high with his private and ecclesiastical commissions. The artist resigned from his teaching position to focus his undivided attention on commissioned works. He was tasked with producing a range of works for the 19th centenary of the arrival of St Paul in Malta (1960), a project on which fellow artist Gabriel Caruana collaborated by providing light design and composition works.

The heavy tension and political-religious crisis which overtook Malta at the time had its effects on the artist, whose strong style became ideally suited for ecclesiastical art. Cremona’s work for the centenary depicted St Paul as a warrior, a stark deviation from the customary image of the saint. The image of St Paul, wielding a sword, is striking and assertive, reminiscent of Mario Sironi’s futurist and brutalist arrangements. A stately, pictorial and august composition constructed using jagged lines, strong cubes and jarring shades, St Paul’s image has strong futurist features and gives viewers a sense that the saint was a military man.

The Glass Collage

The 1960s marked a dramatic response to Cremona’s work, seeing the birth of some of Cremona’s best works. Cremona’s career took a turn from the two decades of landscape paintings, futuristic abstractions and brutalist-inspired compositions. Cremona started producing his impasto compositions, constructed with a spectrum of materials like gravel, cloth, sand, cement and glass. The series was influenced by the world around Cremona, with striking influences from the works of Arte Povera masters like Alberto Burri, Piero Manzoni and Manolo Millares. Notably, Cremona started creating these works right around the time of Malta’s Independence — an occasion which supplied local creatives with a feeling of individuality like never before.

Cremona cemented his work through an imposing memorial housed at De La Salle College — a portrait of the Lasallian founder swathed in a deluge of mosaic, standing at a staggering height of 10.6 meters. Over 100,000 tesserae were utilised by the artist, who also used an outstanding 120 distinct hues in the behemoth masterwork.

The artist disentangled himself from the decades of creating art controlled by external parties and committees; he could finally produce what he desired. He finally created a tapestry of pieces which would become the antecedents to a project which took the Maltese art world by storm — the Glass Collage series.

Cremona took part in the Artists’ National Guild exhibition at the National Museum, Valletta, during which he delivered his Development into Space series — an abstract sequence which formed part of the Glass Collage series. That same year, he organised a solo exhibition titled Exhibition of Paintings by Emvin Cremona, during which the Glass Collage series was formally presented to the public — the process of transformation, newly-found cognition and annihilation through creation and vice versa, stupefied the public, to say the least. The works were made up of shattered glass, pulverised pigments, paint poured on materials and a snarl of colours, lines, glass, impasto, cement and a range of conflicting energies which formed a complex, frivolous but controlled image.

Through this new series, Cremona took the opportunity to interact with faith and chance like never before. This series came about in an interesting period in Cremona’s life — great uncertainty and pressure in both Cremona’s personal life and the Maltese political scene impacted the artist. He was also at the peak of his career, juggling church commissions, stamp design works, organising exhibitions and designing his future family home in Ħ’Attard. He was also commissioned to design the Medal of Merit (later replaced by Ġieħ ir-Repubblika) for the years 1968–1971. The Glass Collage series could even be seen as a relief of sorts for the artist and a way of depicting his newfound independence.

The Later Years

In 1970, Emvin Cremona designed the Malta Pavilion for Expo ‘70, in Osaka, and took part in the collective Richard Demarco Gallery exhibition, Art from Malta, with fellow artists Mary de Piro, Gabriel Caruana and Richard England. One of his works was gifted to Queen Elizabeth II by the National Council of Women. In 1977, he represented Malta at the Commonwealth Artist of Fame exhibition which marked the Queen’s 25th anniversary on the British throne.

Sadly, in the early 1980s, Cremona suffered a stroke, which left him incapable of using his right hand. Nonetheless, he kept on painting and even created five religious works in a different style from his more renowned pieces. Emvin Cremona passed away on the 29th of January 1987, leaving behind him a loving family and a legacy of outstanding works in multiple churches, public spaces and private collections. Despite his early death, the artist achieved a significant deal — his unparalleled style remains recognisable to this day, and his works helped place Malta on a global stage. He was renowned for his geometric figures and abstract compositions, countered with baroque harmonies and opulent colours. His work showcased the union between modernity and convention — a move that not only gladdened the archaic church entity but steered it towards an avant-garde era. Through this consonance, he dominated the field of church art for two decades, presenting inventive concepts and even alleviating the effect of conservativeness in local art. Acclaimed pieces by Cremona embellish churches all over Malta and Gozo — most notably in Għaxaq, Balzan, Nadur, Floriana, Msida, Paola, Ħamrun and Għarb.

Cremona took part in countless exhibitions, four of which were solo exhibitions. He also displayed his work internationally in Venice, Rome, Edinburgh, London, Anzio, Monte Carlo and Amsterdam. During his lifetime, Cremona was awarded a gold medal by the Malta Civil Council, was knighted in the Pontifical Order of St Sylvester and received the Order of Merit and the Golden Medal from the Malta Society of Arts, Manufacture and Commerce. Cremona’s work was presented to the United Nations in New York, and one of his pieces was commissioned for the WHO Headquarters in Geneva.

Commemorations were held to celebrate 100 years from his birth in 2019.